In January 1950, senator Victor Biaka-Boda of French West Africa was touring his homeland when his car broke down in a region with a history of cannibalism.

His charred bones were found in November. Apparently he had been eaten by his constituents.

In January 1950, senator Victor Biaka-Boda of French West Africa was touring his homeland when his car broke down in a region with a history of cannibalism.

His charred bones were found in November. Apparently he had been eaten by his constituents.

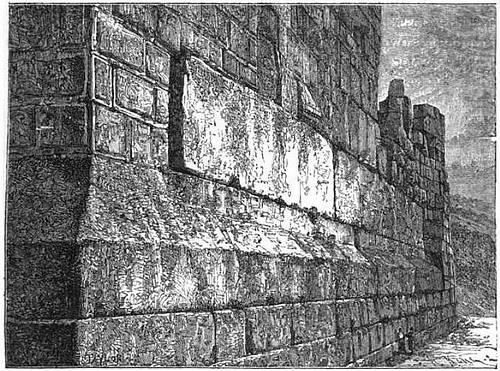

In a quarry at Baalbek, in modern Lebanon, lies “the stone of the south” — a single hewn stone weighing 1500 tons. It’s not surprising that the ancients abandoned it; if they’d got it out of the quarry it would have been the largest stone ever moved.

But a retaining wall nearby contains a row of three stones weighing 750 tons apiece. Somehow they were raised 22 feet into position. No one knows how.

Hiram de Witt, of this town, who has recently returned from California, brought with him a piece of the auriferous quartz rock, of about the size of a man’s fist. On thanksgiving day it was brought out for exhibition to a friend, when it accidentally dropped on the floor, and split open. Near the centre of the mass was discovered, firmly embedded in the quartz, and slightly corroded, a cut-iron nail of the size of a sixpenny nail. It was entirely straight, and had a perfect head. By whom was that nail made? At what period was it planted in the yet uncrystallized quartz? How came it in California? If the head of that nail could talk, we should know something more of American history than we are ever likely to know.

— “Springfield (U.S.) Republican,” quoted in The Latter-Day Saints’ Millennial Star, March 1, 1852

One of the natural curiosities of Hernando County, Florida, is an immense live-oak, situated near Brooksville, which seven feet from the ground measures thirty-five and one half feet in circumference; from this height to the top it has but two large limbs spreading out, and at the top measures eighty yards across. On one side of this singular work of nature is a small orifice from which issues a continual stream of cold air, showing some subterranean connection that is unaffected by what is going on above ground. No matter whether the wind blows east, west, north, or south, there is a constant current of cold air from this mysterious cavity.

— Albert Plympton Southwick, Handy Helps, No. 1, 1886

In March 1893, weary and vexed in his work classifying ancient finger rings, German archaeologist H.V. Hilprecht went to bed and dreamed that a tall priest led him to a Babylonian treasure chamber. The priest explained that the fragments were not finger rings but earrings for a statue of the god Ninib, cut from a votive cylinder sent by King Kirigalzu to the temple of Bel. “If you will put the two together you will have a confirmation of my words,” he said. “But the third ring you have not yet found in the course of your excavations, and you never will find it.”

“With this the priest disappeared,” Hilprecht wrote. “I awoke at once, and immediately told my wife the dream, that I might not forget it. Next morning — Sunday — I examined the fragments once more in the light of these disclosures, and to my astonishment found all the details of the dream precisely verified in so far as the means of verification were in my hands. The original inscription on the votive cylinder read: ‘To the god Ninib, son of Bel, his lord, has Kurigalzu, pontifex of Bel, presented this.'”

(Reported in The American Naturalist, October 1896)

The following circumstance is related in a letter to a friend from Chateau de Venours:–

‘Two persons were on a short journey, and passing through a hollow way, a dog which was with them started a badger, which he attacked, and pursued, till he look shelter in a burrow under a tree. With some pains they hunted him out, and killed him. … Not having a rope, they twisted some twigs, and drew him along the road by turns. They had not proceeded far, when they heard a cry of an animal in seeming distress, and stopping to see from whence it proceeded, another badger approached them slowly. They at first threw stones at it, notwithstanding which it drew near, came up to the dead animal, began to lick it, and continued its mournful cry. The men, surprised at this, desisted from offering any further injury to it, and again drew the dead one along as before; when the living badger, determining not to quit its dead companion, lay down on it, taking it gently by one ear, and in that manner was drawn into the midst of the village; nor could dogs, boys, or men induce it to quit its situation by any means, and to their shame be it said, they had the inhumanity to kill it, and afterwards to burn it, declaring it could be no other than a witch.’

— Pierce Egan, Sporting Anecdotes, Original and Selected, 1822

See also “Monkeys Demanding Their Dead.”

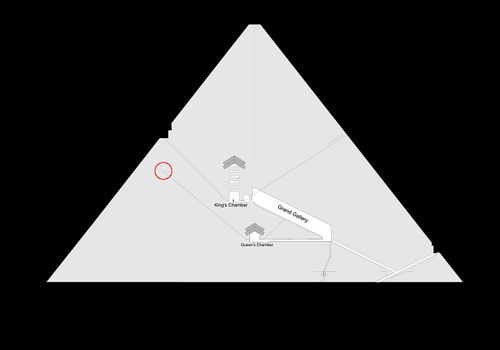

Below the king’s chamber in the Great Pyramid of Giza there’s a smaller room whose purpose is unknown. A narrow shaft ascends to the south from that chamber. It’s only 8 inches wide, too narrow for a human to climb, but in 1992 a German robot crawled 65 meters up the incline and discovered a stone door with copper handles. In 2003 a second robot drilled a hole through that door and discovered a second door behind it.

“It looks to me like it is sealing something,” said Zahi Hawass, head of the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities. “It seems that something important is hidden there.”

What is it? Who knows?

Death plays tricks in India. Prince Ramendra Narayan Roy died in Darjeeling in 1909 and turned up alive 12 years later in Dhaka. He didn’t remember the details, he said; he’d been found lying in the jungle and had wandered India as a religious ascetic until his memory had returned.

The Board of Revenue offered proof that Roy had been cremated, but the prince’s tenants believed the claimant and supported his bid for the old estate. Hundreds of witnesses testified variously through 10 years of legal wrangling, which ultimately decided in favor of the mysterious stranger.

His vindication was short-lived, though. Hours after the final hearing, the claimant had a fatal stroke — and, this time, he stayed dead.

See also The Tichborne Claimant.

A queer exhumation was made in the Strip Vein coal bank of Capt. Lacy, at Hammondsville, Ohio, one day last week. Mr. James Parsons and his two sons were engaged in making the bank, when a huge mass of coal fell down, disclosing a large smooth slate wall, upon the surface of which were found, carved in bold relief, several lines of hieroglyphics. Crowds have visited the place since the discovery and many good scholars have tried to decipher the characters, but all have failed. Nobody has been able to tell in what tongue the words were written. How came the mysterious writing in the bowels of the earth where probably no human eye has ever penetrated? There are several lines about three inches apart, the first line containing twenty-five words. Attempts have been made to remove the slate wall, and bring it out, but upon tapping the wall it gave forth a sound that would seem to indicate the existence of a hollow chamber beyond, and the characters would have been destroyed in removing it. At last accounts Dr. Hartshorn, of Mount Union College, had been sent for to examine the writing.

— Wellsville Union, quoted in The True Latter Day Saints’ Herald, Jan. 1, 1869

On Aug. 21, 1945, physicist Harry Daghlian accidentally dropped a brick of tungsten carbide into a plutonium bomb core at the Los Alamos National Laboratory. The mass went critical, and Daghlian died of radiation sickness.

Exactly nine months later, physicist Louis Slotin was conducting an experiment on the same mass of plutonium when his screwdriver slipped and the mass again went critical. He too died of radiation sickness.

The mass became known as “the demon core.”