On Aug. 9 each year in the little Alaskan town of Kotzebue, the sun sets twice.

Due to a quirk of the town’s location and time zone, the sun goes down just after midnight on that day—and then again just before the following midnight.

On Aug. 9 each year in the little Alaskan town of Kotzebue, the sun sets twice.

Due to a quirk of the town’s location and time zone, the sun goes down just after midnight on that day—and then again just before the following midnight.

Over water, or a surface of ice, sound is propagated with remarkable clearness and strength. … Lieut. Foster, in the third Polar expedition of Capt. Parry, found that he could hold conversation with a man across the harbor of Port Bowen, a distance of six thousand six hundred and ninety-six feet, or about a mile and a quarter. This, however, falls short of what is asserted by Derham and Dr. Young, — viz., that at Gibraltar the human voice has been heard at the distance of ten miles, the distance across the strait.

— Charles Carroll Bombaugh, Gleanings for the Curious from the Harvest-Fields of Literature, 1890

In March 1876, Scientific American reported that witnesses in northeast Kentucky had observed “flakes of meat” drifting down from a clear sky. The flakes, which were “perfectly fresh,” measured up to 3-4 inches square and were confined to an oblong field.

The Louisville Courier-Journal reported that a local butcher roasted a slice and pronounced it “palatable.” Presumably he did this before hearing the prevailing theories: that lightning had roasted a flock of ducks–and that a flight of buzzards had disgorged its latest meal.

An affecting anecdote was recently recorded in the French papers. A young man took a dog into a boat, rowed to the centre of the Seine, and threw the animal over, with intent to drown him; the poor dog often tried to climb up the side of the boat, but his master as often pushed him back, till, overbalancing himself, he fell overboard. As soon as the faithful dog saw his master in the stream he left the boat, and held him above water till help arrived from the shore, and his life was saved.

— T. Wallis, The Nic-Nac; or, Oracle of Knowledge, 1823

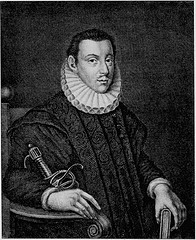

When 17-year-old polymath James Crichton arrived in Paris in 1578 to complete his education, he immediately challenged the faculty of the College of Navarre to a disputation. And he was pretty cocky about it:

He proposed that it should be carried on in any one of twelve specified languages, and have relation to any science or art, whether practical or theoretical. The challenge was accepted; and, as if to show in how little need he stood of preparation, or how lightly he held his adversaries, he spent the six weeks that elapsed between the challenge and the contest, in a continual round of tilting, hunting, and dancing.

“On the appointed day, however, and in the contest, he is said to have encountered all the gravest philosophers and divines, and to have acquitted himself to the astonishment of all who heard him. He received the public praises of the president and four of the most eminent professors. The very next day he appeared at a tilting match in the Louvre, and carried off the ring from all his accomplished and experienced competitors.”

(From Samuel Griswold Goodrich, Curiosities of Human Nature, 1852)

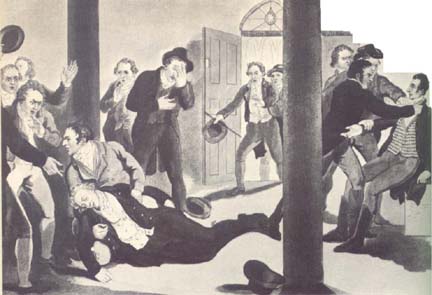

On the night of May 11, 1812, John Williams of Redruth in Cornwall awakened his wife and told her he’d dreamed that he was in the lobby of the House of Commons and saw a man shoot the chancellor. Twice he went back to sleep, and twice he had the same dream.

Williams repeated the experience to friends in the following days, one of whom told him, “Your description is not at all that of the Chancellor, but is certainly very exactly that of Mr. Perceval, the chancellor of the exchequer.” Williams was explaining that he had never met or corresponded with this man when a messenger arrived from Truro with word that Perceval had been shot by an assassin in the lobby of the House of Commons on May 11 — the night of Williams’ dream.

According to a contemporary news account, Williams visited the spot six weeks later: “Immediately that he came to the steps at the entrance of the lobby, he said, ‘This place is as distinctly within my recollection, in my dream, as any room in my house,’ and he made the same observation when he entered the lobby. He then pointed out the exact spot where Bellingham stood when he fired, and which Mr. Perceval had reached when he was struck by the ball, where, and how he fell. The dress both of Mr. Perceval and Bellingham agreed with the description given by Mr. Williams, even to the most minute particular.”

In 1923, 7-year-old Rosemary Brown said she’d had a vision of a white-haired man in a black gown. “He told me that when I grow up, he would give me music,” she said.

Ten years later she recognized a picture of Franz Liszt. And in 1964, she said he returned, acting “like sort of a reception desk” to put her in touch with dead composers from Grieg to Chopin, who dictated new works to her from beyond the grave.

The classical music establishment gave these mixed marks. Leonard Bernstein and André Previn were skeptical, but Richard Rodney Bennett said, “If she is a fake, she is a brilliant one, and must have had years of training.” (She claimed to have had only three years of piano instruction.) “Some of the music is awful, but some is marvelous. I couldn’t have faked the Beethoven.”

Whatever the truth, the experiment is over now. Brown died in 2001, presumably joining her illustrious friends — and depriving them of an audience here below.

In his Lives (1827), Peter Walker recounts a baffling spectacle seen on Scotland’s River Clyde in the summer of 1686:

[T]here were showers of bonnets, hats, guns, and swords, which covered the trees and the ground; companies of men in arms marching in order upon the water-side; companies meeting companies, going all through other, and then all falling to the ground and disappearing: other companies immediately appeared, marching the same way.

Walker says these reports continued for at least three afternoons, but notes that fully a third of the assembled crowd, including himself, could see nothing. That sounds like a mass delusion, but “those who did see, told what works (i.e. locks) the guns had, and their lengths and wideness, and what handles the swords had … and the closing knots of the bonnets.” Make up your own mind.

In the year 1796, died at Wordley Workhouse, Berks, Mary Pitts, aged 70; on being accused of having rummaged the box of another pauper, she wished God might strike her dead if she had; and instantly expired.

— Kirby’s Wonderful and Scientific Museum, 1803

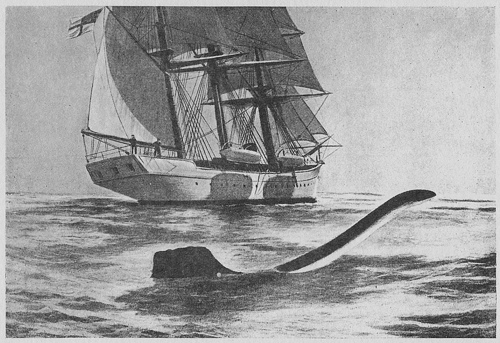

On Dec. 7, 1905, British naturalists J. Nicoll and E.G.B. Meade-Waldo spotted “a creature of most extraordinary form and proportions” during a research cruise off the coast of Brazil. Nicoll described a head “shaped somewhat like that of a turtle” above a 6-foot “eel-like” neck that “lashed up the water with a curious wriggling movement.” Below the water “we could indistinctly see a very large brownish-black patch, but could not make out the shape of the creature.”

They later spied it doing about 8.5 knots, slightly faster than the ship: “From the commotion in the water it looked as if a submarine was going along just below the surface.” The witnesses insisted it was not a whale, though Nicoll felt it was a mammal. That’s all we know.