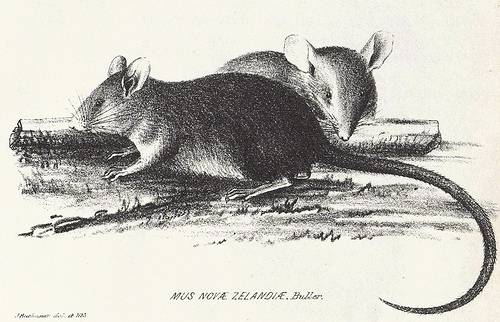

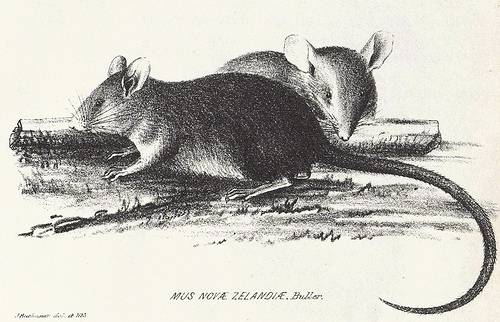

In the ecclesiastical courts of 16th-century France, lawyer Bartholomew de Chasseneux made his name by prosecuting the local vermin (“O snails, caterpillars, and other obscene creatures, which destroy the food of our neighbours, depart hence!”).

Impressed with his argument, the authorities in Autun asked him to advocate for the rats, which they put on trial in 1510 for eating the harvest of Burgundy.

That’s a tall order for even a master lawyer, but, amazingly, Chasseneux won the day:

In his defence, Chasseneux showed that the rats had not received formal notice; and, before proceeding with the case, he obtained a decision that all the priests of the afflicted parishes should announce an adjournment, and summon the defendants to appear on a fixed day.

At the adjourned trial, he complained that the delay accorded his clients had been too short to allow of their appearing, in consequence of the roads being infested with cats. Chasseneux made an able defence, and finally obtained a second adjournment. We believe that no verdict was given.

(From Sabine Baring-Gould, Curiosities of Olden Times, 1896)