On June 11, 1920, bridge expert Joseph Elwell was found dead in his Manhattan home, a bullet between his eyes. All the windows and doors were fastened except for Elwell’s bedroom window on the third floor. There was no evidence of a break-in, nothing of value was missing, and ballistics evidence ruled out suicide. The case has never been solved.

Oddities

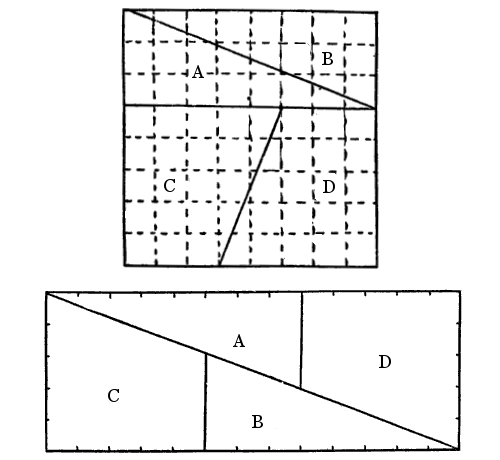

More Geometry Trouble

The top figure, measuring 8 × 8, can be reassembled to form the bottom figure, measuring 5 × 13. Thus 64 = 65.

Privacy

There is a secret chamber at the old Cumberland seat of the ancient family of Senhouse. To this day its position is known only by the heir-at-law and the family solicitor. This room at Nether Hall is said to have no window, and has hitherto baffled every attempt of those not in the secret to discover its whereabouts.

Remarkable as this may seem in these prosaic days, it has been confirmed by the present representative of the family, who, in a communication to us upon the subject, writes as follows: ‘It may be romantic, but still it is true that the secret has survived frequent searches of visitors. There is no one alive who has been in it, that I am aware, except myself.’

— Allan Fea, Secret Chambers and Hiding-Places, 1908

First Things First

In 1963, Giants pitcher Gaylord Perry joked, “They’ll put a man on the moon before I hit a home run.”

On July 20, 1969, just minutes after Apollo 11 made its lunar landing, he hit the first home run of his career.

Worst Trip Ever

The ‘Mermaid,’ Colonial Government cutter, left Sydney for Raffles Bay, but on entering Torres Straits she got on shore, and was lost. All on board were saved upon a rock. In three days afterwards the ‘Swiftsure,’ Captain Johnson, which sailed from Tasmania, hove in sight, and took on board the captain and crew of the ‘Mermaid,’ but in three days she also got on shore, and was wrecked. Two days afterwards the ‘Governor Ready,’ also from Hobart Town, Tasmania (April 2), passing within sight, took the shipwrecked people belonging to the ‘Mermaid’ and ‘Swiftsure’ on board; but was itself wrecked on May 18, but all the people saved by taking refuge in the long boats. The ship ‘Comet,’ also from Tasmania, soon after took the whole of the collected crews of the lost ships ‘Mermaid,’ ‘Swiftsure,’ and ‘Governor Ready’ on board, but was herself wrecked, but all hands saved. At last the ship ‘Jupiter,’ from Tasmania, came in sight, and taking all on board, steered for Port Raffles, at the entrance to which harbour she got on shore, and received so much damage that she may be said to have been wrecked. 1829.

— John Henniker Heaton, Australian Dictionary of Dates and Men of the Time, 1879

The Un-Hoax

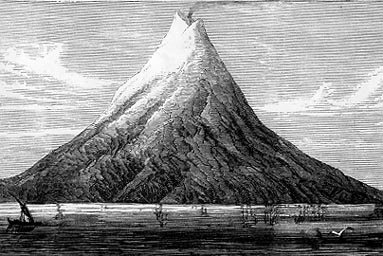

In 1883, the assistant telegraph editor of the Boston Globe invented the story of a volcanic eruption in the South Pacific, purportedly related by the captain of a freight steamer. Editorial writer Florence Finch Kelly later recalled:

The tale he told was truly one of horrific happenings — what looked like a whole island blown into the sky, showers of ashes that darkened the sunlight and covered his decks inches deep, great blocks of ice in the midst of red-hot streams of lava, the ocean bubbling with heat from these torrents of fire, tons of fish killed by the heated ocean water and floating dead on its surface, and many another marvel fit to make even a tough old sea captain’s eyes pop from his head.

The story filled several columns on the Globe‘s front page, and it was picked up in New York, London, and Chicago. Only later did reports arrive of a catastrophe in Indonesia: “With his imaginary volcanic eruption, Mr. Soames had closely hit in time and place the explosion of Krakatoa, the greatest volcanic eruption of modern times, and in his account he had included many phenomena that were paralleled in later descriptions of the actual outburst! Did the vagaries of chance ever direct the long arm of coincidence to a more amazing result?”

(UPDATE: In Media Hoaxes [1989], Fred Fedler reports that the editor’s story was based on early cables from London regarding the volcano’s eruption. He embellished the cables’ scant information with surmised details based on library research, and these proved to be surprisingly accurate. So the truth is much less impressive than Kelly’s account — or than that published by Frank Edwards in two books in the 1950s.)

Spite House

In 1882, New Yorker Joseph Richardson found himself with a plot of land that was only 5 feet wide, at Lexington Avenue and 43rd Street. He offered to sell it for $5,000, but the buyer offered only $1,000. Richardson called him a tightwad and vowed to put up an apartment building of his own.

He managed to fit eight three-room suites into the four-story structure. (“Everybody is not fat,” he said, “and there will be room enough for people who are not circus or museum folk.”) The dining tables were 18 inches wide, and only one resident at a time could use the stairs. Even visitors found it an ordeal: One summer day in the 1890s, reporter Deacon Terry of the American became wedged in a stairway while trying to reach Richardson on the roof; he was finally forced to slip out of his clothes and interviewed the landlord in his underwear.

Nonetheless, the building stood for 33 years. It was torn down in 1915.

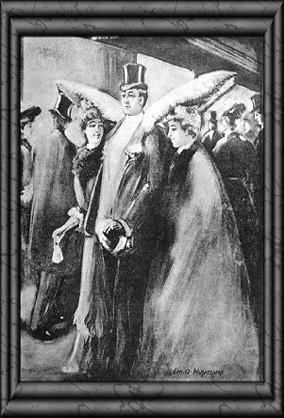

Social Comment

An illusion, of sorts. Step back from the screen.

Noted

Henry Welby, an eccentric character, confined himself in an obscure house in London, where he remained unseen by any one until his death, a period of 44 years. He died in 1636.

— Bizarre Notes & Queries, April 1886

Literary Reunions

Browsing in a Paris bookshop in the 1920s, the novelist Anne Parrish came upon an old copy of Jack Frost and Other Stories, a favorite from her childhood in Colorado. When she showed it to her husband, he found it was her own copy, inscribed with her name and address.

George Bernard Shaw once came across one of his own books in a used bookstore in London. He was surprised to find his own inscription inside — he had presented the book “with esteem” to a friend. He immediately bought the book and had it wrapped and delivered again, after adding a second inscription: “With renewed esteem, George Bernard Shaw.”