On Oct. 17, 1917, the sailing schooner Zabrina was found hard aground on the Cherbourg Peninsula in northwestern France. She had sailed from the English port of Falmouth two days earlier and should have made fast passage across the English Channel. No trace of her four-man crew was ever found.

Oddities

Stretch

In the Philosophical Transactions for 1712, W. Cheselden, a celebrated anatomist, describes the dimensions of some human bones of an extraordinary size, which were dug up near St. Alban’s, in Hertfordshire. The circumference of the skull lengthwise was twenty-six inches, and its breadth twenty-three inches. The greatest diameter of each os innominatum was twelve inches. The left os femoris was twenty-four inches long, and the right one was twenty-three inches in length. Each tibia was twenty-four inches long. If all the parts bore a due proportion, this man must have been eight feet high. The bones were found near an urn, inscribed ‘Marcus Antoninus,’ on the site of a Roman camp.

— Edward J. Wood, Giants and Dwarfs, 1868

“Lizard in an Egg”

“In July 1822, the wife of the man who superintends the decoy ponds in the parish of Great Oakley, near Harwich, took an egg from a hen’s nest, in which was a remarkable discolouration. She kept it about a week, and, upon breaking it, observed something within alive, which so alarmed her, that she let it fall, and ran for her husband who was close by, and immediately came, and found lying on the ground, surrounded with the contents of the egg, an animal of the lizard species alive, but incapable, from weakness, of getting away. The contents of the egg were fœtid, contained a very small portion of yolk, and with the albumen, not more than sufficient to half fill the shell. The animal proved to be a land swift, speckled belly, about four inches in length, nothing remarkable in its form, except its hind legs being longer than usual. It died shortly after being out of the egg. The man has it dried for the inspection of the curious.”

— Colchester Gazette, cited in The Cabinet of Curiosities, 1824

Gifted

German prodigy Jean-Philippe Baratier squeezed a lifetime’s work into less than two decades. Born in 1721 to a Huguenot minister near Nuremberg, he was polyglot from birth — his father spoke to him only in Latin, his mother in French, and the servants in High Dutch. By age 5 he was reading the Old and New Testaments in Greek and translating them into Latin and Hebrew. He matriculated at Altorf at 10, and three years later he was introduced to the king of Prussia and received into the Royal Academy. His interests expanded into navigation, astronomy, and history, including the Thirty Years’ War, the succession of bishops of Rome, and an inquiry into Egyptian antiquities. When he died at age 19, he left behind 11 published works and 26 manuscripts.

The New World Prophecy

There’s a passage in Seneca’s Medea that seems to have foretold the discovery of America 1400 years before the event:

Venient annis secula seris,

Quibus Oceanus vincula rerum.

Laxet, et ingens pateat tellus

Tethysque novos detegat orbes

Nec sit terris ultima Thule.

“The times will come in later years when ocean may relax the chain of things, and a vast continent may open; the sea may uncover new worlds, and Thule cease to be the last of lands.”

“An ‘Angry Tree'”

The ‘angry tree,’ a woody plant which grows from ten to twenty-five feet high, and was formerly supposed to exist only in Nevada, has recently been found both in eastern California, and in Arizona, says the Omaha Bee. If disturbed, this peculiar tree shows signs of vexation, even to ruffling up of its leaves like the hair on an angry cat, and giving forth an unpleasant, and sickening odor.

— Miscellaneous Notes and Queries, 1892

The Brass Menagerie

Amongst the curiosities of his day, Walchius mentions an iron spider of great ingenuity. In size it did not exceed the ordinary inhabitants of our houses, and could creep or climb with any of them, wanting none of their powers, except, of which nothing is said, the formation of the web. Various writers of credit, particularly Kircher, Porta, and Bishop Wilkins, relate that the celebrated Regiomontanus, (John Muller,) of Nuremberg, ventured a loftier flight of art. He is said to have constructed a self-moving wooden eagle, which descended toward the Emperor Maximilian as he approached the gates of Nuremberg, saluted him, and hovered over his person as he entered the town. This philosopher, according to the same authorities, also produced an iron fly, which would start from his hand at table, and after flying round to each of the guests, returned as if wearied, to the protection of his master.

— Cabinet of Curiosities, Natural, Artificial, and Historical, 1822

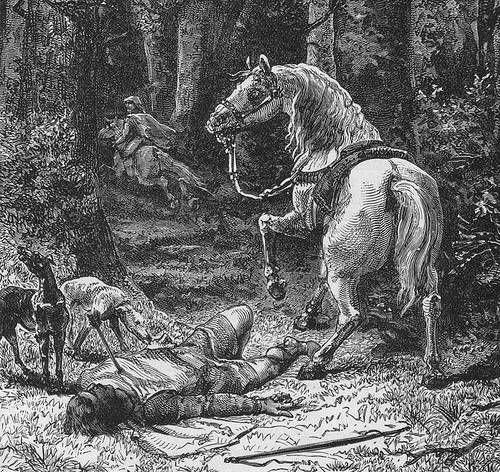

Cold Case

A son of William the Conqueror, William II of England is remembered mostly for the curious manner of his death. In August 1100, William organized a hunting expedition in the New Forest. In sharing arrows with the Anglo-Norman nobleman Walter Tirel, he said, “It is only right that the sharpest be given to the man who knows how to shoot the deadliest shots.” That was tempting fate, apparently: The king did not return after the hunt, and his body was discovered the next day with an arrow piercing his lungs.

Walter fled to France, but chroniclers generally don’t consider him a murderer. He was a skilled bowman, unlikely to fire impetuously, and the abbot who sheltered him in France heard him swear repeatedly that he had not been in the part of the forest where the king was hunting. On the other hand, William’s brother Henry was also in the hunting party, and he stood to gain (and did) from William’s death.

So what really happened? We’ll never know.

“Intermarriage”

Mr. Hardwood had two daughters by his first wife, the eldest of whom was married to John Coshick: this Coshick had a daughter by his first wife whom old Hardwood married, and by her had a son; therefore John Coshick’s second wife could say:

My father is my son, and I’m my mother’s mother;

My sister is my daughter, and I’m grandmother to my brother.

— The Cabinet of Curiosities, 1824

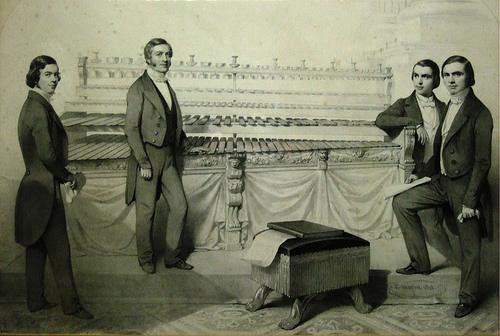

The Musical Stones of Skiddaw

In 1827, Keswick stonemason Joseph Richardson noticed that certain rocks in Britain’s Lake District gave a pure, ringing tone. After 13 years of effort he produced a lithophone, an arrangement of tiered rocks that one struck with mallets, and he took it on a three-year concert tour through Northern England.

It’s not clear what it sounded like: Richardson and his three sons played Mozart, Beethoven, and Handel, reportedly achieving different effects by striking the stones in different ways. An 1846 newspaper account says the tone varied from the warble of a lark to the bass of a funeral bell. Richardson called it “the resource of a shipwrecked Mozart.”

By 1848 they were performing for the queen and traveling to France, Germany, and Italy. On the eve of a trip to America, though, the youngest son died of pneumonia, and the band retired. Richardson’s great-grandson donated the instrument to a museum in 1917.