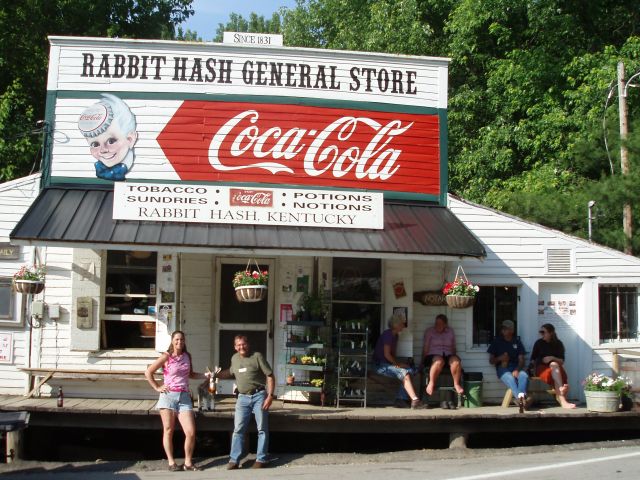

Rabbit Hash, Ky., has been governed by dogs since 1998. The hamlet’s first elected mayor was a dog “of unknown parentage” named Goofy Borneman-Calhoun, who was inaugurated in 1998 and died in office in July 2001. He was succeeded by Junior Cochran, a black Labrador elected in 2004. When Junior also died in office, a special election installed Lucy Lou, a border collie and the town’s first female mayor, who was named Best Elected Official in 2013 by Cincinnati CityBeat magazine and reportedly considered a presidential run in 2015.

The 2016 election went to a pit bull named Brynneth “Brynn” Pawltro, and the town’s historical society also recognized the runners-up, an Australian shepherd and a border collie, as ambassadors who might step in if Brynn were unable to make an appearance.

The current mayor, a French bulldog named Wilbur Beast, took office last year, with a beagle and a golden retriever joining the border collie as ambassadors.

Wilbur’s human, Amy Noland, told NBC News that she ran his campaign because of “all of the negative media that’s out there surrounding America, and the election, and COVID-19, so I guess I wanted Wilbur to be something positive in the news. … He’s done a lot of interviews locally, he’s had a lot of pets, a lot of belly scratches and a lot of ear rubs.”