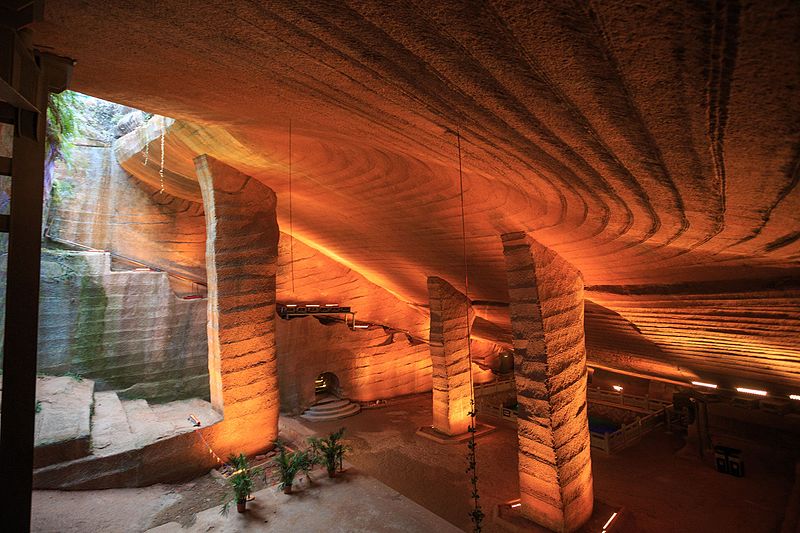

In 1924 architect Frederick Kiesler proposed a house fashioned as a continuous shell rather than an assembly of columns and beams:

The house is not a dome, but an enclosure which rises along the floor uninterrupted into walls and ceilings. Thus the safety of the house does not depend on underground footings but on a strict coordination of all enclosures of the house into one structural unit. Even the window areas are not standardized in size or shape, but are, rather, large and varied in their transparency and translucency, and form part of the continuous flow of the shell.

Storage space is provided between double shells in the walls, radiant heating is built into the floor, and there are no separate bathrooms, as bathing is done in the individual living quarters.

“While the concept of the house does not advocate a ‘return to nature’, it certainly does encourage a more natural way of living, and a greater independence from our constantly increasing automative way of life.”

(Via Ulrich Conrads, The Architecture of Fantasy: Utopian Building and Planning in Modern Times, 1962.)