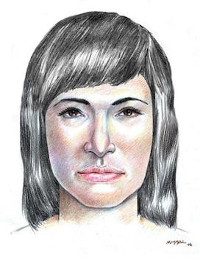

In November 1970, a man and his daughters came upon the charred remains of a woman in the foothills near Bergen, Norway. Some personal items were nearby, and two suitcases were later found at the railway station, but all identifying marks had been removed from all of these.

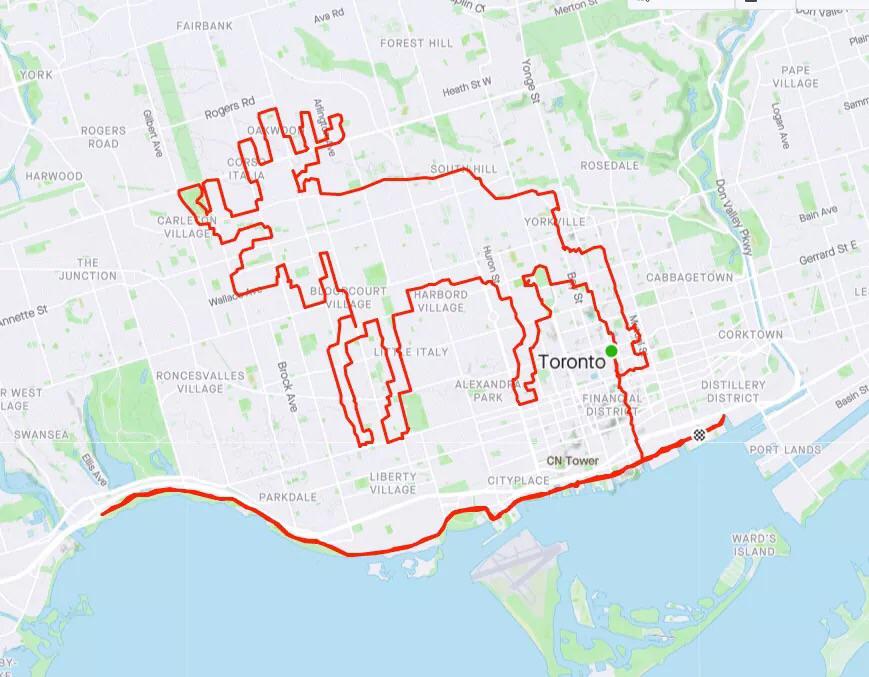

An autopsy showed the woman had been incapacitated by phenobarbital and poisoned by carbon monoxide, and she’d consumed 50 to 70 sleeping pills. A notepad found in one of the suitcases suggested that she’d traveled throughout Europe using at least eight false identities. She’d last been seen alive when she’d checked out of her room at the Hotel Hordaheimen two days earlier; she’d paid in cash and requested a taxi. During her stay she’d appeared guarded and kept to her room.

The woman has never been identified. Her death was attributed to the sleeping pills, and she was interred in a Bergen graveyard. A 2017 analysis of her teeth suggested that she’d been born in Germany around 1930 and had perhaps moved to France as a child. In 2005 a resident of Bergen said he’d seen a woman hiking on a hillside outside town five days before the discovery of the body, dressed lightly and followed by two men. She’d seemed about to speak to him but had not. He’d reported the encounter to the police, but no investigation was made.