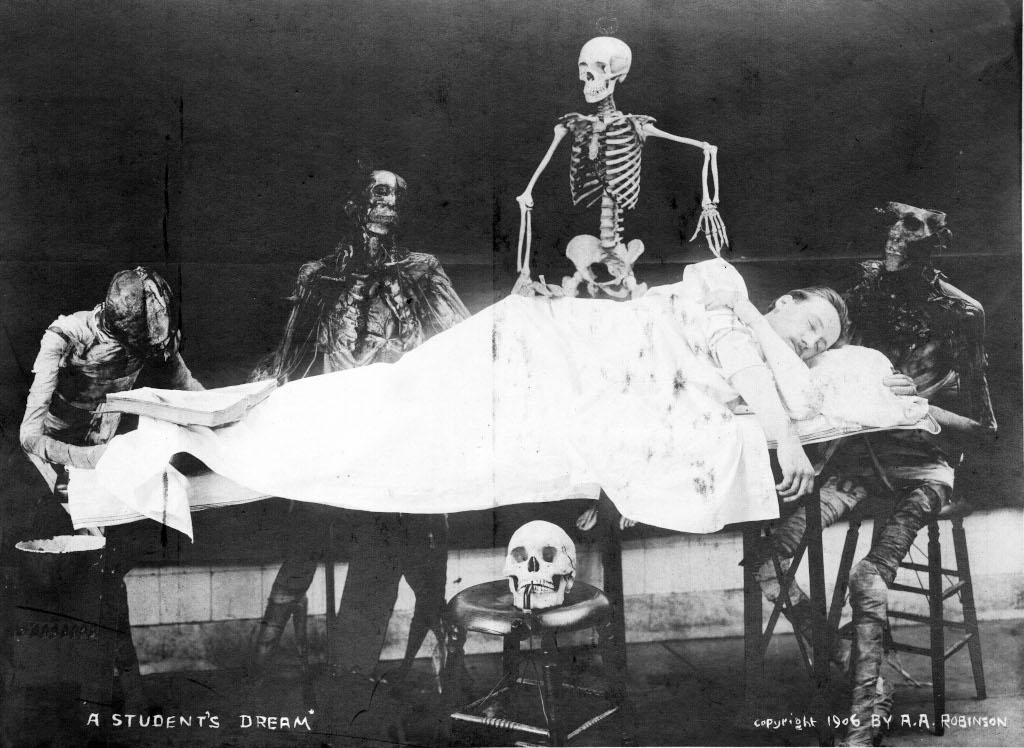

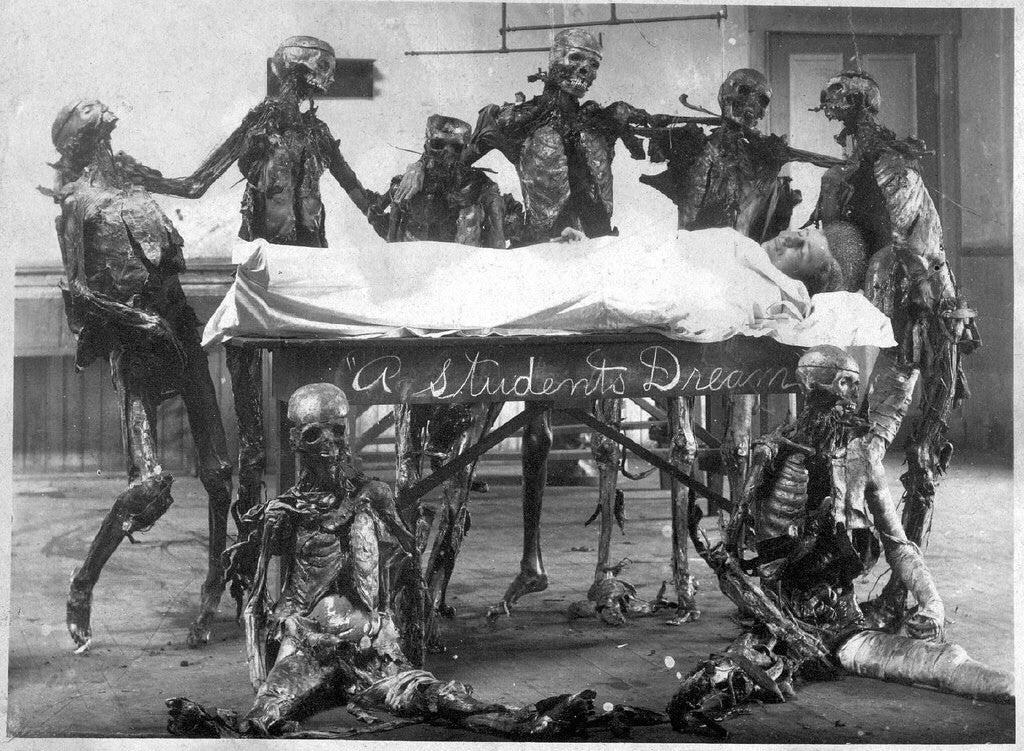

In the early 20th century, medical students often posed for photographs with the cadavers they were learning to dissect — in some cases even trading places with them for a tableau called “The Student’s Dream.”

John Harley Warner and James M. Edmonson have published a book of these photos, Dissection: Photographs of a Rite of Passage in American Medicine 1880-1930. “What we know with certainty about any particular photograph often is frustratingly meager,” they write. “A dissection room photograph discovered tucked between the pages of an old anatomy textbook or up for auction on eBay is likely to have no indication of where or when it was taken, who took it, or who is in it. The photographs suggest stories that cannot easily be recovered.”

But they say that the images generally were intended not to be entertaining or flippant, but to mark a professional rite of passage for the students. “Privileged access to the body marked a social, moral, and emotional boundary crossing. ‘Know thy Self’ inscribed on the dissecting table, the Delphic injunction nosce te ipsum, could refer to the shared corporeality of dissector and dissected. But it most certainly referred to knowing the new sense of self acquired through these rites. As visual memoirs of a transformative experience, the photographs are autobiographical narrative devices by which the students placed themselves into a larger, shared story of becoming a doctor.”