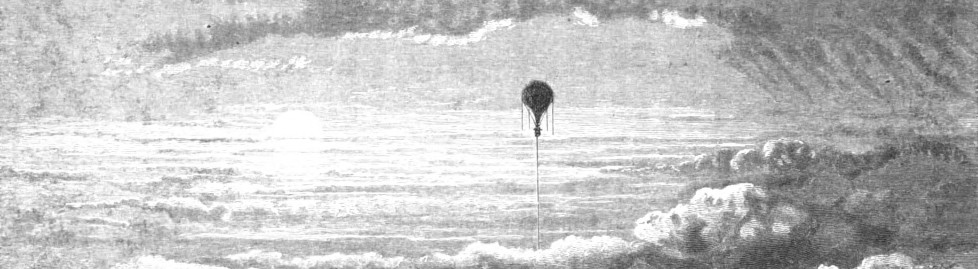

In June 1867 French astronomer Camille Flammarion was floating west from Paris in a balloon when he entered a region of dense cloud:

Suddenly, whilst we are thus suspended in the misty air, we hear an admirable concert of instrumental music, which seems to come from the cloud itself and from a distance of a few yards only from us. Our eyes endeavour to penetrate the depths of white, homogeneous, nebulous matter which surrounds us in every direction. We listen with no little astonishment to the sounds of the mysterious orchestra.

The cloud’s high humidity had concentrated the sound of a band playing in a town square more than a kilometer below. Five years earlier, during his first ascent over Wolverhampton in July 1862, James Glaisher had heard “a band of music” playing at an elevation of nearly 4 kilometers (13,000 feet).

(From Glaisher’s Travels in the Air, 1871.)