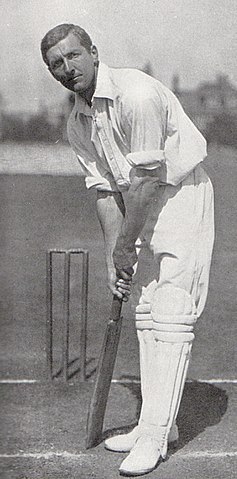

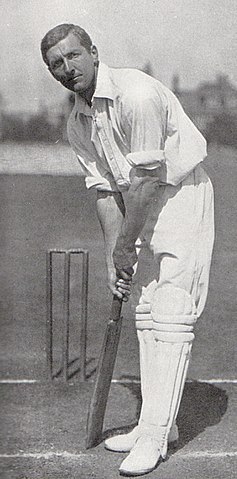

English cricketer C.B. Fry had a curious party trick: He would stand on the floor facing a mantelpiece, crouch, and leap upward, turning in midair and landing with his feet planted on the shelf, from which he would bow to onlookers. He claimed to be able to do this into his 70s.

On July 17, 1933, John Dillinger walked into the Daleville Commercial Bank in Indiana and told the teller, “Well, honey, this is a holdup. Get me the money.” Told there was no key to the teller’s cage, Dillinger vaulted over the counter himself to investigate. “This would become another of his well-known trademarks,” writes John Beineke in Hoosier Public Enemy, “the quick and graceful vaults over counters that were often several feet high. The feat earned him the nickname ‘Jackrabbit’ in some newspapers.”

In a letter to the Times on March 16, 1944, G.M. Trevelyan, the Master of Trinity College, Cambridge, remarks on the tradition of trying to leap up the eight semicircular steps of the college hall at one bound. “The only person to succeed of whom I know was the gigantic [William] Whewell, when he was Master of the college; he clapped his mortar-board firmly on his head, picked up his gown with one hand, and leapt.”

Trevelyan had recently learned that Henry Hutchinson Montgomery, later a bishop, had made the jump during his undergraduate career at Trinity, between 1866 and 1870, and “I have heard that the feat was accomplished once or twice in this century; once, I was told, an American succeeded, but I have not the facts or names. It has certainly been done very seldom.”

(Thanks, Chris.)