abscede

v. to move away or apart; to lose contact; to separate

anachorism

n. something located in an incongruous position

longinquity

n. greatness of distance; remoteness

aerumnous

adj. troubled; distressed

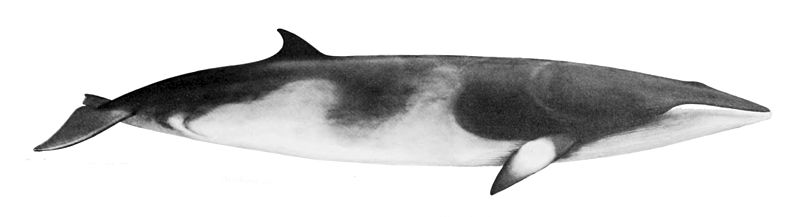

In 2007 Brazilian villagers were surprised to discover a 16-foot minke whale on a sandbank in the Tapajos River, 1,000 miles from the sea. Apparently it had got separated from its group in the Atlantic and swum up the Amazon.

After two days, rescuers managed to return it to the water. “What we can definitely say is that it lost its way,” biologist Fabia Luna told Globo television. “It entered the river, which on its own is unusual. But then to have travelled around 1,500 kilometers is both strange and adverse.”

Brazil’s environmental agency said the whale might have been in the region for two months before it was spotted. “It is outside of its normal habitat, in a strange situation, under stress, and far from the ocean,” said whale expert Katia Groch. “The probability of survival is low.”