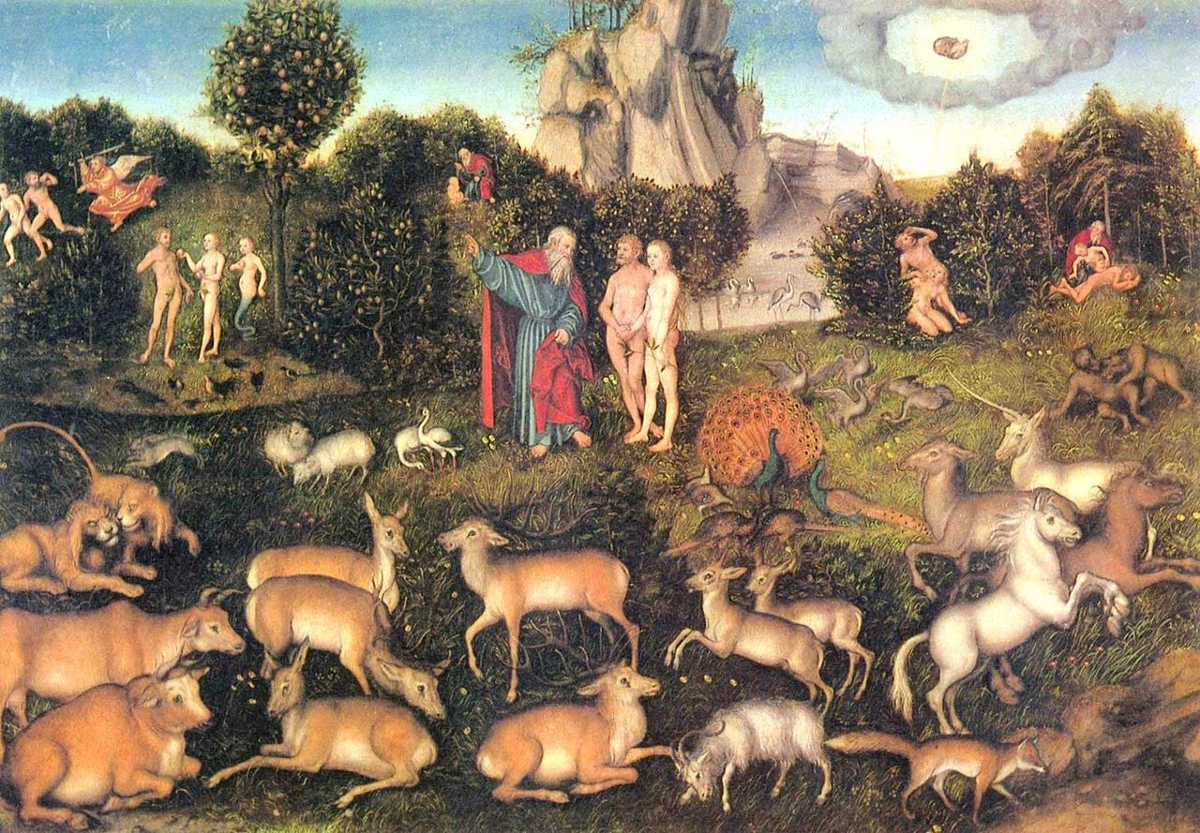

Obscure but interesting: In his 1857 history of the West Branch Valley of the Susquehanna River, John Franklin Meginness quotes a 1793 indenture that purports to trace the title to a plot of Pennsylvania land back to the creation of mankind:

Whereas, the Creator of the earth, by parole and livery of seisin, did enfeoff the parents of mankind, to wit, Adam and Eve, of all that certain tract of land, called and known in the planetary system by the name of The Earth, together with all and singular the advantages, woods, waters, water-courses, easements, liberties, privileges, and all others the appurtenances whatsoever thereunto belonging, or in any wise appertaining to have and to hold to them the said Adam and Eve, and the heirs of their bodies lawfully to be begotten, in fee-tail general forever, as by the said feoffment recorded by Moses, in the first chapter of the first book of his records commonly called Genesis, more fully and at large appears on reference being thereunto had …

This goes on for four pages, tracing ownership through the Six Nations of North America to William Penn and finally to one Flavel Roan, the “witty and rather eccentric gentleman” who Meginness says drew up the deed. “His education was good, and his penmanship superior.”