Wallsend Metro station is located near the Segedunum Roman fort at the end of Hadrian’s Wall, which marked the northern limit of the Roman empire at the time of its construction in 122 A.D.

Accordingly its signs are rendered in Latin.

Wallsend Metro station is located near the Segedunum Roman fort at the end of Hadrian’s Wall, which marked the northern limit of the Roman empire at the time of its construction in 122 A.D.

Accordingly its signs are rendered in Latin.

When Hirschau, Bavaria starting mining kaolinite a century ago, it faced a problem — one of the byproducts of kaolinite is quartz sand, which began piling up in enormous quantities. Fortunately sand itself has multiple uses — in the early 1950s an enterprising skier tried slaloming down the mountain, and soon the dune had its own ski club.

Today the 35-million-tonne “Monte Kaolino” even hosts the Sandboarding World Championships. And, unlike other ski resorts, it’s open in summer.

During World War II one of the most surprising advocates of war bonds was Tommy Tucker, an Eastern gray squirrel who toured the nation in a humiliating wardrobe of 30 dainty costumes. (“THOUGH TOMMY IS A MALE SQUIRREL HE HAS TO WEAR FEMININE CLOTHES BECAUSE TAIL INTERFERES WITH HIS WEARING PANTS,” Life reported defensively.)

Tommy had been adopted in 1942 by the Bullis family of Washington D.C., who took him on the road in their Packard automobile, where he performed for schoolchildren, visited hospitals, and gave uninspiring radio interviews. Between appearances Zaidee Bullis would bathe him and place him in a specially made bed. At the height of his fame his fan club numbered 30,000 members.

Tommy retired after the war but gamely endured further travels with the family. When he died in 1949 he was stuffed and mounted “with his arms out so you could pull the clothes over him,” and his nightmarish fate pursued him even into the grave. He stands today in a display case in a Maryland law office — in a pink satin dress and pearls.

Thailand’s Wat Pa Maha Chedi Kaew has a unique distinction among Buddhist temples: It’s made of beer bottles. When the building was begun in the 1980s, the monks were seeking ways to encourage waste disposal and promote environmentalism. They had been collecting beer bottles since 1984 and decided to use them as a building material.

The main temple, completed in 1986, comprises about 1.5 million bottles. The monks say they provide good lighting, are easy to clean, and retain their color — the green bottles are Heineken and the brown ones are the Thai beer Chang. They even use the bottle caps to make mosaics of the Buddha.

The monks have gone on to build a complex of 20 buildings, everything from a water tower to a crematorium, from the same material. Abbot San Kataboonyo told the Telegraph: “The more bottles we get, the more buildings we make.”

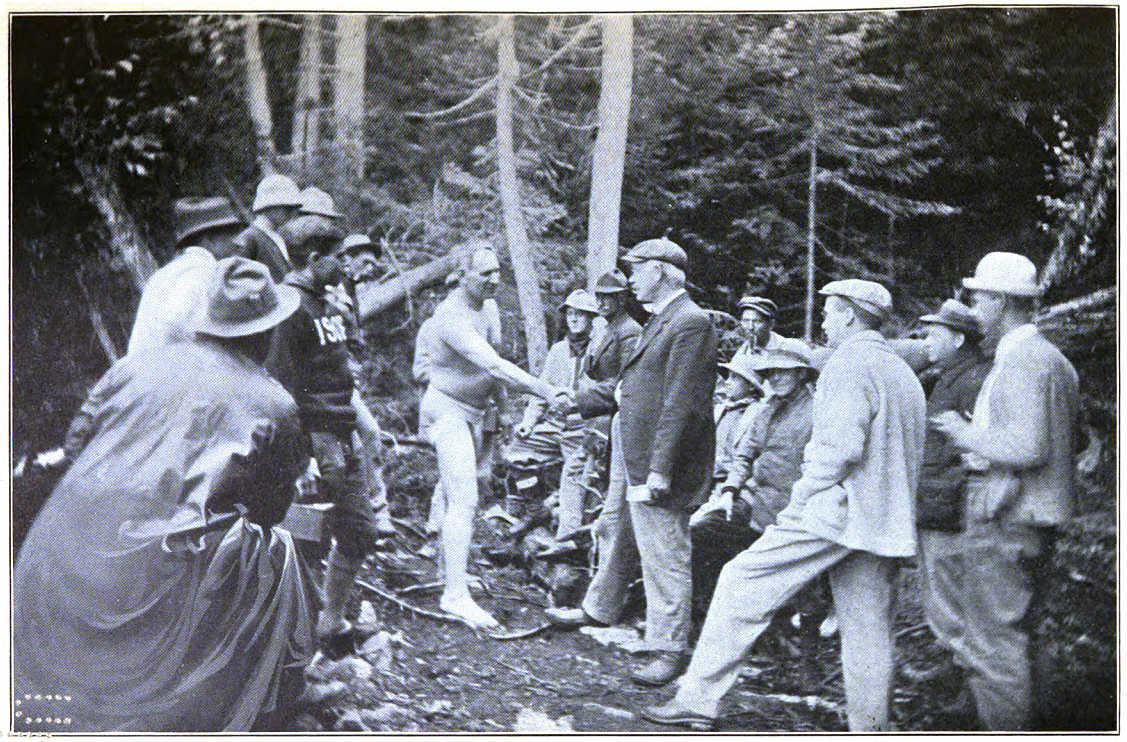

In 1913 outdoorsman Joseph Knowles pledged to spend two months in the woods of northern Maine, naked and alone, fending for himself “without the slightest communication or aid from the outside world.” In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll follow Knowles’ adventures in the woods and the controversy that followed his return to civilization.

We’ll also consider the roots of nostalgia and puzzle over some busy brothers.

In 1953, 150 golfers participated in a “Golden Ball” competition in which they teed off at the first tee at Cill Dara Golf Club in Kildare, Ireland, and holed out at the 18th hole at the Curragh, about 5 miles away. A prize of £1 million was offered for a hole in one, which would have been well earned, as the distance is 8,800 yards.

In The Book of Irish Golf, John Redmond writes, “The hazards to be negotiated included the main Dublin-Cork railway line and road, the Curragh racecourse, Irish army tank ranges and about 150 telephone lines.” The trophy went to renowned long hitter Joe Carr, who covered the distance in 52 shots.

In 1920, Rupert Lewis and W. Raymond Thomas played over 20 miles of countryside from Radyr Golf Club near Cardiff, Wales, to Southerndown Golf Club at Ewenny, near Bridgend. Most onlookers guessed that they’d need at least 1,000 strokes, but they completed the journey in 608, playing alternate strokes. “At one time, the pair had to wade knee deep to ford a river,” writes Jonathan Rice in Curiosities of Golf, “but dried out by jumping a hedge while being chased by a bull.”

Inspired by the P.G. Wodehouse story “The Long Hole,” eight members of the Barnet Rugby Hackers Golf Club played 23 miles across Ayrshire in 1968, from Prestwick, the site of the first Open Championship, to Turnberry, the site of that year’s event. They lost “only” 50 or 60 balls while negotiating “a holiday camp, a dockyard, a stately home, a croquet lawn, several roofs, the River Doon,” and another bull, for a final score of 375 to 385.

N.T.P. Murphy gives a few more in A Wodehouse Handbook: In 1913 two golfers played 26 miles from Linton Park near Maidstone to Littleston-on-Sea in 1,087 strokes; Doe Graham played literally across country in 1927, from Florida’s Mobile Golf Club to Hollywood, a distance of 6,160,000 yards (I don’t have the final score, but he’d taken 20,000 strokes by the time he reached Beaumont, Texas); and Floyd Rood played from the Atlantic to the Pacific in 1963 in 114,737 shots.

The object of golf, observed Punch in 1892, “is to put a very small ball into a very tiny and remotely distant hole, with engines singularly ill adapted for the purpose.”

03/25/2017 UPDATE: Reader Shane Bennett notes that Australia’s Nullarbor Links claims to be the world’s longest golf course — players drive from Ceduna in South Australia to Kalgoorlie in Western Australia, stopping periodically to play a hole. Par for the 18 holes is only 73, but the course stretches over 1,365 kilometers. (Thanks, Shane.)

The Icelandic fishing village of Flateyri was devastated when an avalanche buried 17 homes in 1995. To guard against further trouble, they built an earthen dam in the shape of an enormous A.

It worked: An avalanche struck the dam’s eastern wing in February 1999, and another struck the western wing the following March. Both were deflected harmlessly into the sea.

pernicity

n. swiftness, quickness, agility

discoverture

n. the state of not having a husband

supersalient

adj. leaping upon

desponsate

adj. married

The Fenway Millionaires also have a ‘sleeper’ in Norm Zauchin, a massive fellow just out of the Army. Don’t underestimate him. When he was at Birmingham he pursued a twisting foul ball into a front row box. He clutched frantically. He missed grabbing the ball but he did grab a girl, Janet Mooney. This might not be considered a proper introduction by Emily Post but it worked for Zauchin. He married the gal. Nope. Don’t underestimate an opportunist like that.

— Arthur Daley, “Life Among the Millionaires,” New York Times, March 11, 1954

Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” played with Glock pistols by Vitaly Kryuchin, president of the Russian Federation of Practical Shooting, from the 1979 Soviet TV miniseries The Meeting Place Cannot Be Changed. He also plays “Old MacDonald Had a Farm” and the traditional Russian song “Murka.” It’s probably safest not to make requests.

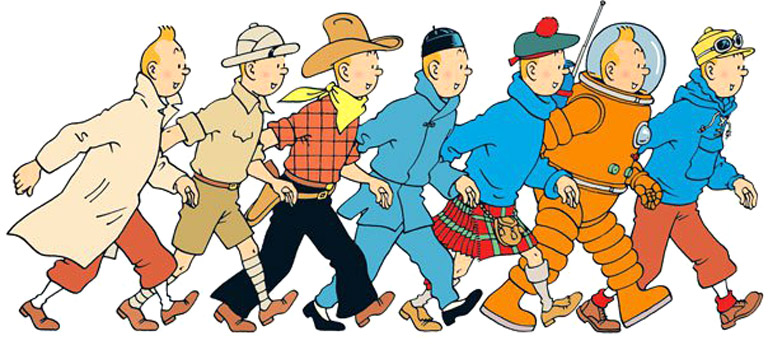

Comic strips offer even more opportunities for working with the symbolism of direction. W.A. Wagenaar, a psychologist at Leiden University and a Tintin fan, once tallied up all the acts and transitions in three Tintin books and discovered that in three out of four cases the characters move from left to right, even when their movement takes several frames to portray. More interestingly still, movements towards the left almost always have a bad outcome. The man who moves his finger from right to left to ring Tintin’s doorbell falls unconscious on the doormat as soon as the alert reporter opens the door. When Captain Haddock crosses the frame from right to left in an attempt to escape, he is recaptured in no time. And so on. This is Tintin’s Law, and it is reminiscent of the messenger in the theatre of the ancient world: entering on the right — and therefore moving towards the left — is a sign to the audience that something ominous is happening.

— Rik Smits, The Puzzle of Left-Handedness, 2010

(Wagenaar’s paper is “Als Kuifje naar links beweegt is er iets mis,” NRC Handelsblad, Aug. 5, 1981.)