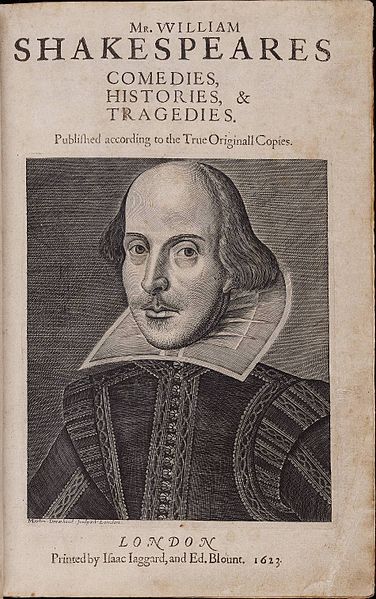

This is the so-called Droeshout portrait of William Shakespeare, engraved by Martin Droeshout as the frontispiece for the First Folio, published in 1623. In his 1910 book Bacon Is Shake-Speare, Edwin Durning-Lawrence draws attention to the fit of the coat on the figure’s right arm. “Every tailor will admit that this is not and cannot be the front of the right arm, but is, without possibility of doubt, the back of the left arm.” Compare this with the figure’s left arm, where “you at once perceive that you are no longer looking at the back of the coat but at the front of the coat.”

If that’s not enough, note the line beneath Shakespeare’s jaw, suggesting that he’s wearing a false face. The engraving is in fact “a cunningly drawn cryptographic picture, shewing two left arms and a mask” and proving that Shakespeare is a fraud and not the author of the plays attributed to him.

I’ll admit that I don’t quite see the problem with the coat, but apparently I’m just not discerning enough: In 1911 Durning-Lawrence reported that the trade journal Tailor and Cutter had agreed that Droeshout’s figure “was undoubtedly clothed in an impossible coat composed of the back and front of the same left arm.” Indeed, the Gentleman’s Tailor Magazine printed “the two halves of the coat put tailor fashion, shoulder to shoulder” and observed that “it is passing strange that something like three centuries should have been allowed to elapse before the tailor’s handiwork should have been appealed to in this particular manner.”