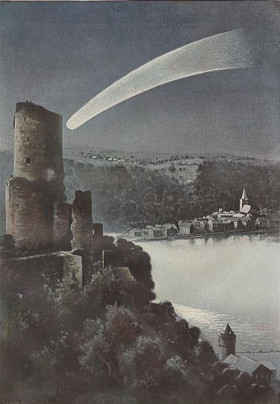

A thousand miles off the coast of West Africa, where the equator crosses the prime meridian, lies a nonexistent point of land known as Null Island. It was invented by GIS analysts to help trap errors: When software converts misspelled street names, bad building numbers, and other faulty data into coordinates of latitude and longitude, the result is often 0°N 0°E — which led cartographers to joke that there’s a 1-square-meter island in the Gulf of Guinea where all these lost features reside. (In fact what’s there is a weather observation buoy, above, which must wonder what all the fuss is about.)

Related: Conceptual artists Terry Atkinson and Michael Baldwin considered a map on which the areas that we normally call Arizona, New Hampshire, Tennessee, etc., are instead labeled “Not Arizona,” “Not New Hampshire,” and “Not Tennessee.” This would have to be regarded as simply false, or at least as inviting new names for these places.

“Yet such a scheme would be correct if, for example, the delineated area normally named Arizona was labelled ‘Not New York’ and so on throughout the whole map synopsis. Only this time the map would be a map to indicate what was not where rather than the conventional what is where. Where there is no road in a certain place we do not conventionally indicate this fact upon the relevant map by labelling it ‘There is no road at this point.'”

(From Jeffrey Kastner and Brian Wallis, Land and Environmental Art, 1998.)