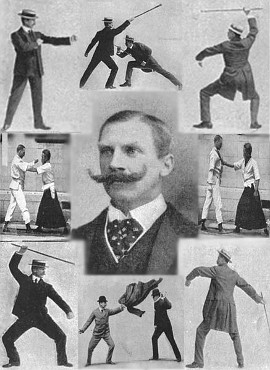

When engineer E.W. Barton-Wright returned to England after three years in Japan, he brought with him a new discipline: Bartitsu, a martial art of his own devising that combined jujutsu, judo, boxing, and stick fighting. He listed its essential principles in an article in Pearson’s Magazine in March 1899:

1. To disturb the equilibrium of your assailant.

2. To surprise him before he has time to regain his balance and use his strength.

3. If necessary to subject the joints of any part of his body, whether neck, shoulder, elbow, wrist, back, knee, ankle, etc. to strain which they are anatomically and mechanically unable to resist.

The combination of systems, he wrote, “can be very terrible in the hands of a quick and confident exponent. One of its greatest advantages is that the exponent need not necessarily be a strong man, or in training, or even a specially active man in order to paralyse a very formidable opponent, and it is equally applicable to a man who attacks you with a knife, or a stick, or against a boxer; in fact, it can be considered a class of self-defence designed to meet every possible kind of attack, whether armed or otherwise.”

In 1899 Barton-Wright established an academy in London to promote the new art, but he proved an indifferent promoter and the school closed its doors within three years. His eccentric fighting style might have been forgotten entirely but for one immortal mention: In The Adventure of the Empty House, when asked how he defeated Professor Moriarty in their climactic struggle at the Reichenbach Falls, Sherlock Holmes credits “baritsu, or the Japanese system of wrestling, which has more than once been very useful to me.”