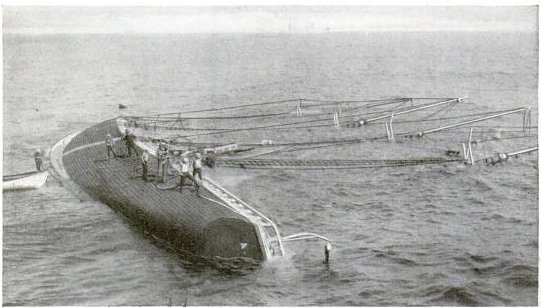

In 1929 the schooner A. Ernest Mills sank after a collision off the coast of North Carolina.

Four days later it bobbed to the surface again. Its cargo of salt had dissolved.

In 1929 the schooner A. Ernest Mills sank after a collision off the coast of North Carolina.

Four days later it bobbed to the surface again. Its cargo of salt had dissolved.

In the summer of 1978, four men rowed a small boat into the deep water off Dassen Island, South Africa, to fish for barracuda. When mist overtook them, they weighed anchor and tried to return to shore, but visibility dropped so quickly that they were soon lost.

Mac Macgregor was in the bow, trying to peer through the mist, when he felt a bump on the right-hand side and discovered two dolphins there, repeatedly forcing the bow to the left, where two more dolphins were swimming.

“I realized that the dolphins’ odd behavior could be significant and shouted to Mr. [Kobus] Stander to steer to the left,” Macgregor said. “Mr. Stander pulled the tiller round wildly and we just managed to graze past the rocks.”

They continued some further distance through the mist, the dolphins continuing to force the prow to the left, and presently they just missed some further rocks — again on the right. “I was getting a strange feeling that we ought to leave our destiny to the dolphins,” Stander said, “since it was clear they had twice prevented us from running on to the rocks.”

The dolphins led the boat for half an hour until it entered calm water, then played around it briefly and disappeared. “When the mist cleared and the houses of Ysterfontein could be discerned, we were speechless,” Stander said. “We had intended going ashore at Dassen Island. We had never dreamed that the dolphins would guide us to Ysterfontein.”

In 1972, when her cabin cruiser sank in the Indian Ocean off Mozambique, a South African woman set out to swim the 25 miles to land. She was trailed by half a dozen sharks, attracted by a cut on her foot. But “as the sharks circled closer … two dolphins appeared at her side,” the New York Times reported. “The young woman, Yvonne Vladislavich, said that the dolphins guarded her against marauding sharks, escorted her as she swam and helped her stay afloat when her strength was failing.” They protected her until she was able to climb onto a buoy, from which she was later rescued.

(“Dolphins Rescue Fishermen,” South African Panorama, August 1978; “South African Reports a Rescue by Dolphins,” New York Times, Sept. 10, 1972.)

While Paulet St. John, Esq., was fox hunting in September 1733, his horse plunged into a chalk pit 25 feet deep. The horse survived and went on to win the Hunters’ Stakes at Winchester the following year.

St. John was so impressed that he erected a monument on Farley Mount, where it stands to this day.

He named the horse “Beware Chalk Pit.”

On Sept. 1, 1939, a flock of 850 sheep were bedded down for the night in Pine Canyon in the Raft River Mountains of northwestern Utah when a passing thunderstorm wet both the ground and the animals. A single stroke of lightning killed 835 sheep, 98 percent of the flock.

Similarly (below), two bolts of lightning killed 654 sheep on Mill Canyon Peak in the American Fork Canyon in north-central Utah on July 18, 1918.

So avoid northern Utah. On the other hand:

A ploughman in a field, Reuben Stephenson, of Langtoft, England, was struck down by lightning, when both his horses were killed on the spot, and he was so much injured that his life was at first despaired of. In consequence of the accident, Dr. Allison of Birdlington, attended upon the man, and whilst doing so, found he was suffering from a malignant cancer of the lip. When Mr. Stephenson had sufficiently recovered from the effects of the lightning, an arrangement was entered into for the removal of the cancer by an operation; but, strange to say, just when this was on the point of being performed, a minute inspection was made of the cancer, when it was discovered that from the time of the accident, a healing process had been commenced in the lip; this being so evident, the operation was, of course, not attempted; and, in a moderate space of time, the man was completely cured.

— Lancet, 1855, quoted in Paul Fitzsimmons Eve, A Collection of Remarkable Cases in Surgery, 1857

Why do ghosts wear clothes? If a ghost is the spirit of a living creature, how can it carry its inanimate garments into the afterlife?

“How do you account for the ghosts’ clothes — are they ghosts, too?” asked the Saturday Review in 1856. “What an idea, indeed! All the socks that never came home from the wash, all the boots and shoes which we left behind us worn out at watering-places, all the old hats which we gave to crossing-sweepers … What a notion of heaven — an illimitable old clothes-shop, peopled by bores, and not a little infested with knaves!”

In 1906 psychic researcher Andrew Lang argued that, far from confusing the notion of an afterlife, ghosts’ clothing might even help to corroborate its existence. “A pretty instance occurs, I think, in a biography of Warren Hastings. The anecdote, as I remember it, avers that at a meeting of the Council of the East India Company in Calcutta one of the members (I think several shared the experience) saw his own father, wearing a hat of a peculiar shape, hitherto strange to the observers. In due time came a ship from London bearing news of the father’s death, and a large and well-selected assortment of the new hat fashionable in England. It was the hat worn by the paternal appearance! If the circumstances are recorded in the minutes of the proceedings of the Council, which I have not consulted, then the hat of that spook becomes important as evidence.”

Even if we grant that a dead person can convey his most personal belongings into the afterlife, how are we to account for phantom ships, coaches, and railway trains? In his 1879 book The Spirit World, American spiritualist Eugene Crowell decided that, rather than being the spirits of “dead” earthly conveyances, these are constructed in the afterlife by the ghosts of mariners and railwaymen who want to ply their trades again. Spectral ships “glide over the waves without sinking,” Crowell explained, “and earthly winds propel them at rates of speed which our ships cannot attain.” If that’s true, then perhaps some ghostly tailor is simply manufacturing clothes for the naked spirits of the newly dead. Decent of him.

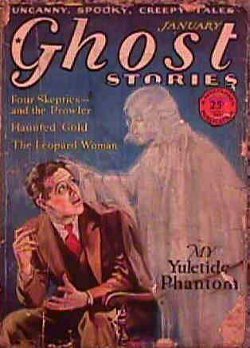

anatiferous

adj. producing ducks or geese

A deservedly rare word; it arises from the medieval belief that the barnacle goose (Branta leucopsis) grew underwater, emerging from barnacles that fell from trees. In his Topographia Hibernica of 1188, Welsh monk Giraldus Cambrensis wrote:

There are likewise here many birds called barnacles,(barnacle geese) which nature produces in a wonderful manner, out of her ordinary course. They resemble the marsh-geese, but are smaller. Being at first, gummy excrescenses from pine-beams floating on the waters, and then enclosed in shells to secure their free growth, they hang by their beaks, like seaweeds attached to the timber. Being in progress of time well covered with feathers, they either fall into the water or take their flight in the free air, their nourishment and growth being supplied, while they are bred in this very unaccountable and curious manner, from the juices of the wood in the sea-water. I have often seen with my own eyes more than a thousand minute embryos of birds of this species on the seashore, hanging from one piece of timber, covered with shells, and, already formed.

Apparently the belief arose because these geese were never seen to nest like other birds; it was not yet understood that birds migrate.

In the Indian state of West Bengal lies a district known as Cooch Behar which is curiously merged with its neighbor, Bangladesh. The Indian land contains 92 Bangladeshi enclaves, and the Bangladeshi land contains 106 Indian enclaves.

The largest Indian enclave itself contains a Bangladeshi enclave, and that Bangladeshi enclave contains a bare hectare of Indian farmland known as Dahala Khagrabari. That makes Dahala Khagrabari the world’s only instance of an enclave in an enclave in an enclave.

See Concentric Landmarks.

01/23/2016 UPDATE: The two countries resolved the confusion in July 2015 by swapping enclaves. The Belgian town of Baarle-Hertog is still entertainingly confusing, though. (Thanks, Dan.)

In 1959, in response to a challenge by a radio station, Norwegian insulation manufacturer Glassvatt transported a three-ton block of ice from the Arctic Circle to the equator without refrigeration.

The block, insulated with wood and glass wool, was loaded onto a truck that made its way south through Europe, crossed by freighter from Marseilles to Algiers, and then crossed the Sahara, evading guerrillas and continually bogging down in the sand.

After three weeks the crew arrived in Lambaréné, Gabon, where they delivered 300 kg of medicine to Albert Schweitzer, and they reached their destination, Libreville, a week later. Amazingly, the ice block had lost only 11 percent of its weight. They cut it up, shared it among the citizens of the equatorial city, and flew back to Norway.

Most of our pleasures come from filling or emptying cavities, and vice versa.

Contributed by Dr. Vincent J. Derbes of New Orleans to More of Mould’s Medical Anecdotes, 1989.

In 1880, 29-year-old Australian geologist Lamont Young set out in a fishing boat to survey the gold fields north of Bermagui in New South Wales. With him were his assistant, two fishermen, and the vessel’s owner. The boat was spotted sailing north the following morning, but it was discovered deserted that afternoon inside a shoal at Mutton Fish Point, 16 kilometers north of Bermagui.

Inside the boat were clothes, books, and research papers belonging to Young and his assistant, whose spectacles were laid out neatly on the seat. The oars and mast had been lashed to supports, but the sails and anchor were missing, and there was a single bullet hole in the starboard side. Near a campfire on the beach nearby were tins of salmon and butter, a jar of honey, half a loaf of bread, and three mother-of-pearl studs. There was no evidence of a struggle, but the copper case of a cartridge was found in the sand 30 yards from the boat.

The Colonial Office offered a reward of 200 pounds for information leading to the location of the missing men, and Young’s father hired a private detective, but the five were never found, and their disappearance has never been explained. The inlet where the boat was found is now named Mystery Bay in their honor.