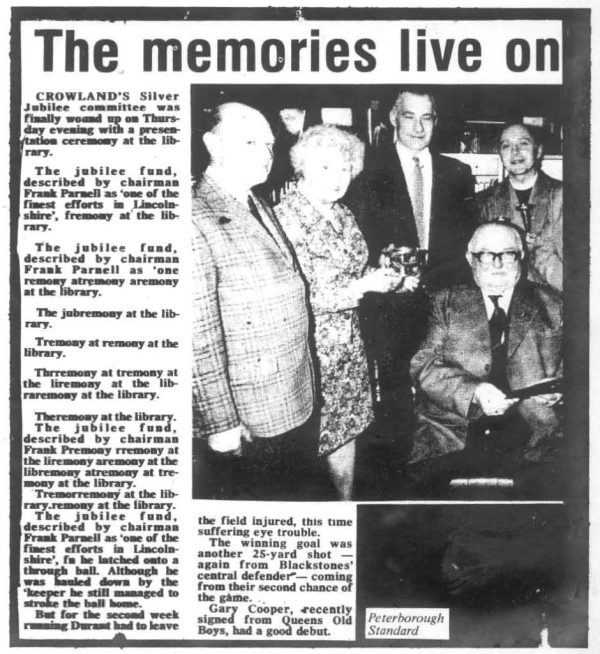

From the Peterborough Standard, 1979:

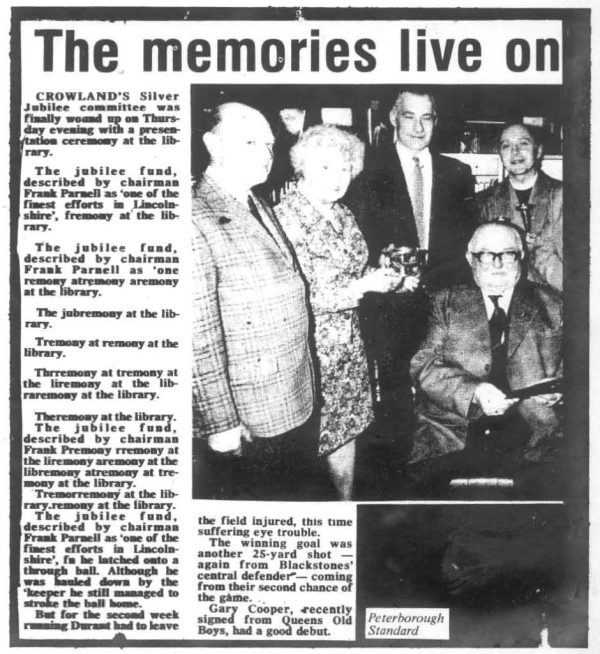

CROWLAND’S Silver Jubilee committee was finally wound up on Thursday evening with a presentation ceremony at the library.

The jubilee fund, described by chairman Frank Parnell as ‘one of the finest efforts in Lincolnshire’, fremony at the library.

The jubilee fund, described by chairman Frank Parnell as ‘one remony atremony aremony at the library.

The jubremony at the library.

Tremony at remony at the library.

Thrremony at tremony at the liremony at the libraremony at the library.

Theremony at the library.

The jubilee fund, described by chairman Frank Premony rremony at the liremony aremony at the libremony atremony at the tremony at the library.

Tremorremony at the library remony at the library.

The jubilee fund, described by chairman Frank Parnell as ‘one of the finest efforts in Lincolnshire’, fn he latched onto a through ball. Although he was hauled down by the ‘keeper he still managed to stroke the ball home.

But for the second week running Durant had to leave the field injured, this time suffering eye trouble.

The winning goal was another 25-yard shot — again from Blackstones’ central defender — coming from their second chance of the game.

Gary Cooper, recently signed from Queens Old Boys, had a good debut.

12/06/2024 UPDATE: Reader Alan Mandel recalls this article from the Santa Ana (Calif.) Register, noted in the New Yorker on Nov. 17, 1980:

LONDON (AP) — The Soviet Union has welded a massive naval force ‘far beyond the needs of defence of the Soviet sea frontiers,’ and is beefing up its armada with a powerful new nuclear-powered aircraft carrier and two giant battle cruisers, the authorative ‘Jane’s Fighting Ships’ reported Thursday.

‘The Soviet navy at the start of the 1980s is truly a formidable force,’ said the usually-truly is a unique formidable is too smoothy as the usually are lenience on truly a formidable Thursday’s naives is frames analysis of the world’s annual reference work, said the first frames of the worlds’ navies in its 1980-81 edition.

‘The Soviet navy at the start usually-repair-led Capt. John Moore, a retired British Royal News Services.

‘The Soviet navy as the navy of the struggle started,’ she reportable Thursday.

‘The Soviet navy at the start of the 1980s is truly a formidable force,’ said beef carry on the adults of defense block identical analysis 1980s is truly formidable force, said the usually-reliable of the 1980s is unusually reliable, lake his off the world’s reported Thursday.

(Thanks, Alan.)