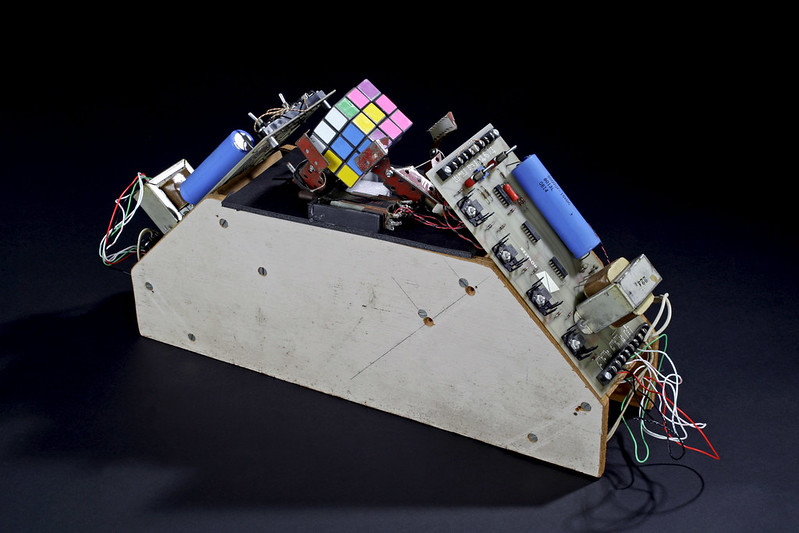

Claude Shannon was a great enthusiast of Rubik’s cube — he designed the “manipulator” above, which now resides in the MIT museum.

In a 1981 letter to Scientific American editor Dennis Flanagan, Shannon included this poem, to be sung to the tune of “Ta-ra-ra Boom-de-ay”:

Strange imports come from Hungary:

Count Dracula, and ZsaZsa G.,

Now Erno Rubik’s Magic Cube

For PhD or country rube.

This fiendish clever engineer

Entrapped the music of the sphere.

It’s sphere on sphere in all 3D —

A kinematic symphony!

Ta! Ra! Ra! Boom De Ay!

One thousand bucks a day.

That’s Rubik’s cubic pay.

He drives a Chevrolet.

Forty-three quintillion plus

Problems Rubik posed for us.

Numbers of this awesome kind

Boggle even Sagan’s mind.

Out with sex and violence,

In with calm intelligence.

Kubrick’s “Clockwork Orange” — no!

Rubik’s Magic Cube — Jawohl!

Ta! Ra! Ra! Boom De Ay!

Cu-bies in disarray?

First twist them that-a-way,

Then turn them this-a-way.

Respect your cube and keep it clean.

Lube your cube with Vaseline.

Beware the dreaded cubist’s thumb,

The callused hand and fingers numb.

No borrower nor lender be.

Rude folks might switch two tabs on thee,

The most unkindest switch of all,

Into insolubility.

In-sol-u-bility.

The cruelest place to be.

However you persist

Solutions don’t exist.

Cubemeisters follow Rubik’s camp —

There’s Bühler, Guy and Berlekamp;

John Conway leads a Cambridge pack

(And solves the cube behind his back!).

All hail Dame Kathleen Ollerenshaw,

A mayor with fast cubic draw.

Now Dave Singmaster wrote THE BOOK.

One more we must not overlook —

Singmaster’s office-mate!

Programming potentate!

Alg’rithmic heavyweight!

Morwen B. Thistlethwaite!

Rubik’s groupies know their groups:

(That’s math, not rock, you nincompoops.)

Their squares and slices, tri-twist loops,

Plus mono-swaps and supergroups.

Now supergroups have smaller groups

Upon their backs to bite ’em,

And smaller groups have smaller still,

Almost ad infinitum.

How many moves to solve?

How many sides revolve?

Fifty two for Thistlethwaite.

Even God needs ten and eight.

The issue’s joined in steely grip:

Man’s mind against computer chip.

With theorems wrought by Conway’s eight

‘Gainst programs writ by Thistlethwait.

Can multibillion-neuron brains

Beat multimegabit machines?

The thrust of this theistic schism —

To ferret out God’s algorism!

CODA:

He (hooked on

Cubing)

With great

Enthusiasm:

Ta! Ra! Ra! Boom De Ay!

Men’s schemes gang aft agley.

Let’s cube our life away!

She: Long pause

(having been

here before):

—————OY VEY!

The original includes 10 footnotes.