Joseph-Henri Flacon found the 1804 French Civil Code too dry, so he rewrote it in rhyming verse.

Joseph-Henri Flacon found the 1804 French Civil Code too dry, so he rewrote it in rhyming verse.

In the mid-1990s Jacques Jouet introduced “metro poems,” poems written on the Paris Métro according to a particular set of rules. He explained the rules in a poem:

There are as many lines in a metro poem as there are stations in your journey, minus one.

The first line is composed mentally between the first two stations of your journey (counting the station you got on at).

It is then written down when the train stops at the second station.

The second line is composed mentally between the second and the third stations of your journey.

It is then written down when the train stops at the third station.

And so on.

The poet mustn’t write anything down when the train is moving, and he mustn’t compose anything when the train is stopped. If he changes lines then he must start a new stanza. He writes down the poem’s last line on the platform of the final station.

Jouet’s poem was itself composed in the Métro, according to its own rules. Presumably this type of writing could be done in any subway, but Marc Lapprand notes that the Paris system supports it unusually well: It’s dense, with 368 different stations, including 87 connecting points (or 293 nominal stations, including 55 connecting points) and a fairly short distance between them (543 meters, on average). The average run between two stations in Paris is a minute and a half, which means the poet has to think quickly in order to keep up.

Levin Becker, who tried the technique for his book 2012 Many Subtle Channels, found it surprisingly challenging: “It constrains the space around your thoughts, not the letters or words in which you will eventually fit them: you have to work to think thoughts of the right size, to focus on the line at hand without workshopping the previous one or anticipating the next.”

In April 1996 Jouet wrote a 490-verse poem while passing through every station in the Métro, following an optimized map laid out for him by a graph theorist. “At the end of those fifteen and a half hours,” he wrote, “I was very tired.”

(Jacques Jouet and Ian Monk, “Metro Poems,” AA Files 45/46 [Winter 2001], 4-14.)

I wish she would not ask me if I love the Kitten more than her.

Of course I love her. But I love the Kitten, too; and it has fur.

— Josephine Preston Peabody, The Book of the Little Past, 1908

In this passage from Tennyson’s Morte d’Arthur, the mail-clad Sir Bedivere carries his wounded king down to a lake by a narrow path along a cliff:

Dry clash’d his harness in the icy caves

And barren chasms, and all to left and right

The bare black cliff clang’d round him, as he based

His feet on juts of slippery crag that rang

Sharp-smitten with the dint of armed heels —

And on a sudden, lo! the level lake,

And the long glories of the winter moon.

“This passage is particularly interesting in the sudden change from the harsh imitative sounds describing the trip itself to the peaceful passage, dominated by liquids and nasals, representing the arrival at the shore,” writes Calvin Brown in Music and Literature.

He gives two examples of poets attempting to imitate musical timbres. Detlev von Liliencron’s Die Musik kommt describes the progress of a military band through a little German village:

Klingling, tschingtsching und Paukenkrach,

Noch aus der Ferne tönt es schwach,

Ganz leise bumbumbumbum tsching,

Zog da ein bunter Schmetterling,

Tschingtsching, bum, um die Ecke?

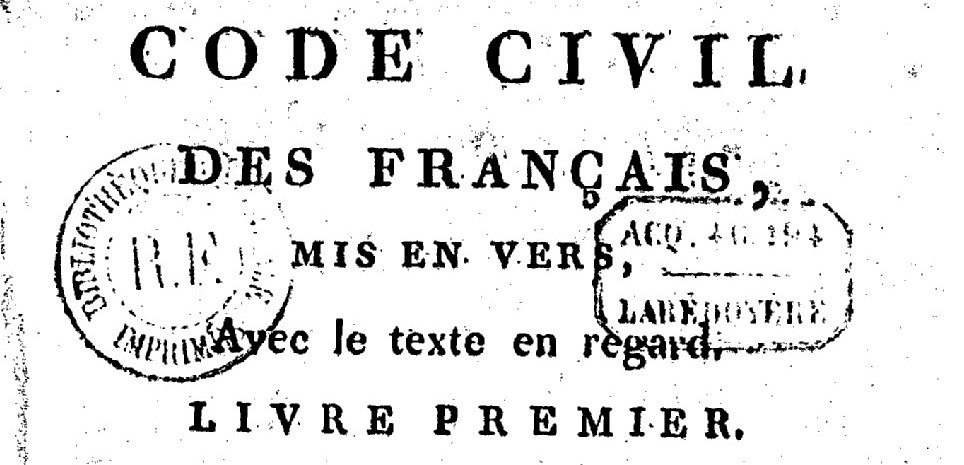

And the first stanza of Paul Verlaine’s Chanson d’automne famously imitates a violin:

Les sanglots longs

Des violons

De l’automne

Blessent mon cœur

D’une langueur

Monotone.

In The Craft of Translation, John Biguenet writes, “English simply has no matching nasal sounds in words that would convey the meaning, unless we turn to trombones, and then we have changed instruments.”

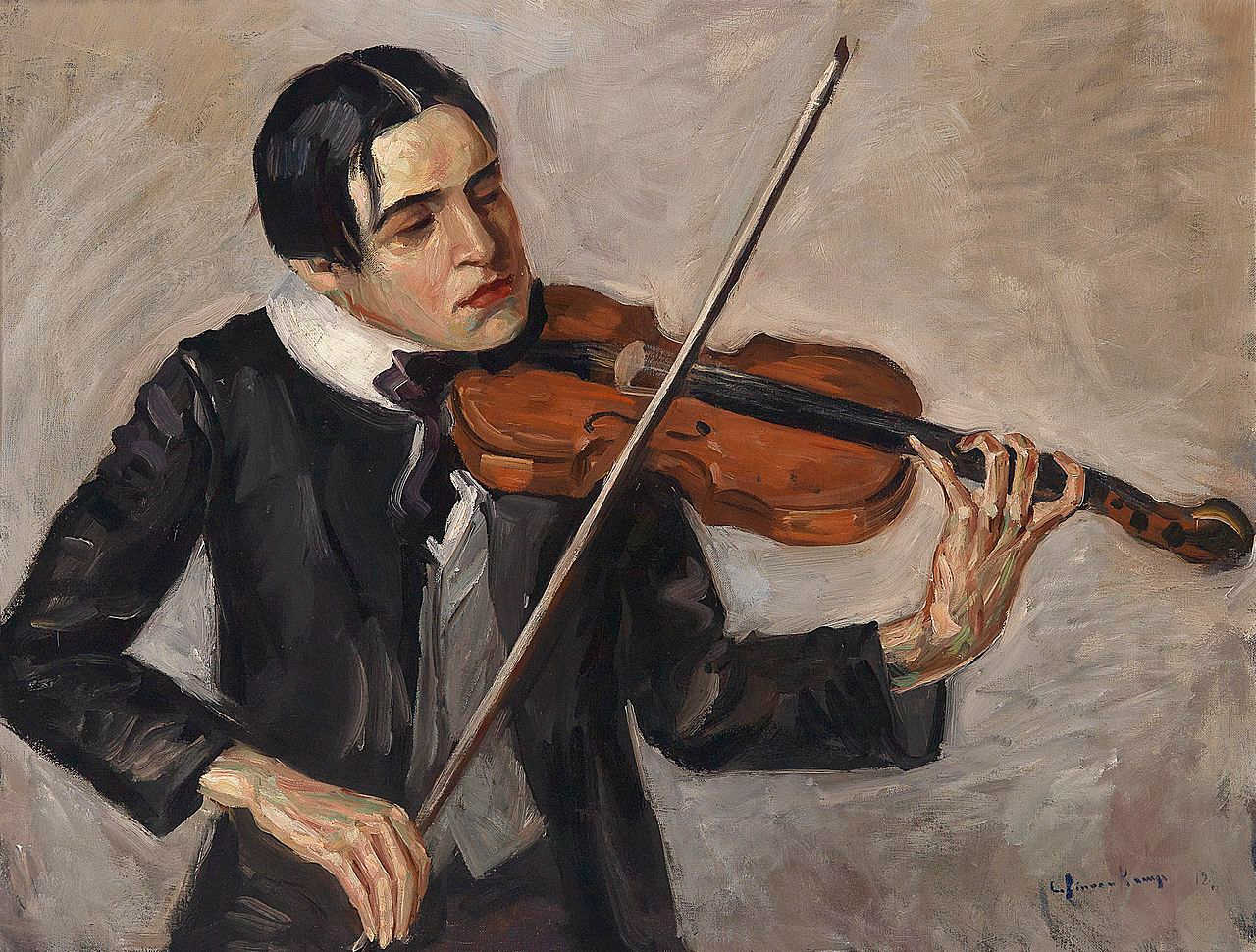

In 2014 England’s University of Sheffield unveiled “the world’s first air-cleansing poem,” four stanzas by literature professor Simon Armitage that are printed on a 10-by-20-meter panel coated with particles of titanium dioxide that use sunlight and oxygen to clear the air of nitrogen oxide pollutants.

“This is a fun collaboration between science and the arts to highlight a very serious issue of poor air quality in our towns and cities,” said science professor Tony Ryan, who collaborated on the project. “This poem alone will eradicate the nitrogen oxide pollution created by about 20 cars every day.”

Armitage said, “Poetry often comes out with the intimate and the personal, so it’s strange to think of a piece in such an exposed place, written so large and so bold. I hope the spelling is right!”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6X7E2i0KMqM

Kurt Schwitters composed this poem in 1922 to show that musical form can be applied to language. The poem consists of four movements (with a cadenza in the fourth), as well as an overture and a finale. Like music it introduces and varies themes — the first movement, in sonata form, develops four main subjects; the largo and the scherzo both have an ABA form; and themes from the first movement reappear in the scherzo. But fundamentally it’s a work of language rather than music — the performer is speaking rather than singing.

“In the first movement I draw your attention to the word for word repeats of the themes before each variation, to the explosive beginning of the first movement, to the pure lyricism of the sung ‘Jüü-Kaa,’ to the military severity of the rhythm of the quite masculine third theme next to the fourth theme, which is tremulous and mild as a lamb, and lastly to the accusing finale of the first movement, with the question ‘tää?'”

Schwitters said he included a written cadenza for those who “had no imagination,” but he preferred that the performer improvise based on the piece’s themes.

accinge

v. to prepare or apply oneself

facetely

adv. elegantly; cleverly; ingeniously

plusquamperfection

n. utter perfection

magnality

n. a great or wonderful thing

A villainous Nazi named Roehm

Was searching for rhymes matching “poem.”

Then, chortling with glee,

Stated that he

Had found one at last. “That’ll show ’em!”

— J.M. Crais

symposiast

n. a member of a drinking party

alate

adj. winged

dimication

n. fighting or strife

bouleversement

n. a turning upside down

“In Other Words,” an airman’s drinking song from World War I:

I was fighting a Hun in the heyday of youth,

Or perhaps ’twas a Nieuport or Spad.

I put in a burst at a moderate range

And it didn’t seem too bad.

For he put down his nose in a curious way,

And as I watched, I am happy to say:

Chorus:

He descended with unparalleled rapidity,

His velocity ‘twould beat me to compute.

I speak with unimpeachable veracity,

With evidence complete and absolute.

He suffered from spontaneous combustion

As towards terrestrial sanctuary he dashed,

In other words — he crashed!

I was telling the tale when a message came through

To say ’twas a poor RE8.

The news somewhat dashed me, I rather supposed

I was in for a bit of hate.

The CO approached me. I felt rather weak,

For his face was all mottled, and when he did speak

Chorus:

He strafed me with unmitigated violence,

With wholly reprehensible abuse.

His language in its blasphemous simplicity

Was rather more exotic than abstruse.

He mentioned that the height of his ambition

Was to see your humble servant duly hung.

I returned to Home Establishment next morning,

In other words — I was strung!

As a pilot in France I flew over the lines

And there met an Albatros scout.

It seemed that he saw me, or so I presumed;

His manoeuvres left small room for doubt.

For he sat on my tail without further delay

Of my subsequent actions I think I may say:

Chorus:

My turns approximated to the vertical,

I deemed it most judicious to proceed.

I frequently gyrated on my axis,

And attained colossal atmospheric speed,

I descended with unparalleled momentum,

My propeller’s point of rupture I surpassed,

And performed the most astonishing evolutions,

In other words — * *** ****!

I was testing a Camel on last Friday week

For the purpose of passing her out.

And before fifteen seconds of flight had elapsed

I was filled with a horrible doubt

As to whether intact I should land from my flight.

I half thought I’d crashed — and half thought quite right!

Chorus:

The machine seemed to lack coagulation,

The struts and sockets didn’t rendezvous,

The wings had lost their super-imposition,

Their stagger and their incidental, too!

The fuselage developed undulations,

The circumjacent fabric came unstitched

Instanter was reduction to components,

In other words — she’s pitched!

(From Peter G. Cooksley, Royal Flying Corps 1914-1918, 2007.)

i'm tired of being a zero vector

i'm tired of being a zero vector

with no direction

no dimension

and no magnitude;

what i need is another element

-- but that would be

a contradiction

of my definition

— Eileen Tupaz, a student at Ateneo University, Quezon City, Philippines, in Crux Mathematicorum 26:6 (June 2000), 337

A poem by Louis Phillips: “If the Modern Artist Ralph Goings Had Met the Poet E.E. Cummings”:

Goings?

Cummings?

Cummings,

Goings.

Goings,

Cummings.

Going,

Goings?

Yep.

Cummings,

Going?

Nope.