When a man’s busy, why, leisure

Strikes him as wonderful pleasure:

‘Faith, and at leisure once is he?

Straightway he wants to be busy.

— Robert Browning

When a man’s busy, why, leisure

Strikes him as wonderful pleasure:

‘Faith, and at leisure once is he?

Straightway he wants to be busy.

— Robert Browning

“What is funny?” you ask, my child,

Crinkling your bright-blue eye.

“Ah, that is a curious question indeed,”

Musing, I make reply.

“Contusions are funny, not open wounds,

And automobiles that go

Crash into trees by the highwayside;

Industrial incidents, no.

“The habit of drink is a hundred per cent,

But drug addiction is nil.

A nervous breakdown will get no laughs;

Insanity surely will.

“Humor, aloof from the cigarette,

Inhabits the droll cigar;

The middle-aged are not very funny;

The young and the old, they are.

“So the funniest thing in the world should be

A grandsire, drunk, insane,

Maimed in a motor accident,

And enduring moderate pain.

“But why do you scream and yell, my child?

Here comes your mother, my honey,

To comfort you and to lecture me

For trying, she’ll say, to be funny.”

— Morris Bishop

Augustus was a chubby lad;

Fat ruddy checks Augustus had;

And every body saw with joy

The plump and hearty healthy boy.

He ate and drank as he was told,

And never let his soup get cold.

But one day, one cold winter’s day,

He scream’d out — “Take the soup away!

O take the nasty soup away!

I won’t have any soup to-day!”

Next day, now look, the picture shows

How lank and lean Augustus grows!

Yet, though he feels so weak and ill,

The naughty fellow cries out still —

“Not any soup for me, I say:

O take the nasty soup away!

I won’t have any soup to-day.”

The third day comes; Oh what a sin!

To make himself so pale and thin.

Yet, when the soup is put on table,

He screams, as loud as he is able, —

“Not any soup for me, I say:

O take the nasty soup away!

I won’t have any soup to-day.”

Look at him, now the fourth day’s come!

He scarcely weighs a sugar-plum;

He’s like a little bit of thread,

And on the fifth day, he was — dead!

![]()

— Heinrich Hoffmann, The Struwwelpeter Painting Book, 1900

When I loved you

And you loved me,

You were the sea,

The sky, the tree.

Now skies are skies,

And seas are seas,

And trees are brown

And they are trees.

— Charles A. Wagner

Ping to me only with thine eyes,

And I will pong with mine;

We twain may win the Challenge cup,

If ping with pong combine:

The craze, that in my soul doth rise,

Is doubtless keen in thine;

I’ll take the rôle of pinger up,

If thou’lt be pongstress mine.

— A Little Book of Ping-Pong Verse, 1902

Victor Hugo’s 1829 poem Djinns is a syllabic snowball — its lines grow progressively longer, then shorter, to reflect the passing of a storm of demons:

Murs, ville,

Et port,

Asile

De mort,

Mer grise

Où brise

La brise,

Tout dort.

Dans la plaine

Naît un bruit.

C’est l’haleine

De la nuit.

Elle brame

Comme une âme

Qu’une flamme

Toujours suit!

La voix plus haute

Semble un grelot.

D’un nain qui saute

C’est le galop.

Il fuit, s’élance,

Puis en cadence

Sur un pied danse

Au bout d’un flot.

La rumeur approche.

L’écho la redit.

C’est comme la cloche

D’un couvent maudit;

Comme un bruit de foule,

Qui tonne et qui roule,

Et tantôt s’écroule,

Et tantôt grandit,

Dieu! la voix sépulcrale

Des Djinns! … Quel bruit ils font!

Fuyons sous la spirale

De l’escalier profond.

Déjà s’éteint ma lampe,

Et l’ombre de la rampe,

Qui le long du mur rampe,

Monte jusqu’au plafond.

C’est l’essaim des Djinns qui passe,

Et tourbillonne en sifflant!

Les ifs, que leur vol fracasse,

Craquent comme un pin brûlant.

Leur troupeau, lourd et rapide,

Volant dans l’espace vide,

Semble un nuage livide

Qui porte un éclair au flanc.

Ils sont tout près! – Tenons fermée

Cette salle, où nous les narguons.

Quel bruit dehors! Hideuse armée

De vampires et de dragons!

La poutre du toit descellée

Ploie ainsi qu’une herbe mouillée,

Et la vieille porte rouillée

Tremble, à déraciner ses gonds!

Cris de l’enfer! voix qui hurle et qui pleure!

L’horrible essaim, poussé par l’aquilon,

Sans doute, ô ciel! s’abat sur ma demeure.

Le mur fléchit sous le noir bataillon.

La maison crie et chancelle penchée,

Et l’on dirait que, du sol arrachée,

Ainsi qu’il chasse une feuille séchée,

Le vent la roule avec leur tourbillon!

Prophète! si ta main me sauve

De ces impurs démons des soirs,

J’irai prosterner mon front chauve

Devant tes sacrés encensoirs!

Fais que sur ces portes fidèles

Meure leur souffle d’étincelles,

Et qu’en vain l’ongle de leurs ailes

Grince et crie à ces vitraux noirs!

Ils sont passés! – Leur cohorte

S’envole, et fuit, et leurs pieds

Cessent de battre ma porte

De leurs coups multipliés.

L’air est plein d’un bruit de chaînes,

Et dans les forêts prochaines

Frissonnent tous les grands chênes,

Sous leur vol de feu pliés!

De leurs ailes lointaines

Le battement décroît,

Si confus dans les plaines,

Si faible, que l’on croit

Ouïr la sauterelle

Crier d’une voix grêle,

Ou pétiller la grêle

Sur le plomb d’un vieux toit.

D’étranges syllabes

Nous viennent encor;

Ainsi, des arabes

Quand sonne le cor,

Un chant sur la grève

Par instants s’élève,

Et l’enfant qui rêve

Fait des rêves d’or.

Les Djinns funèbres,

Fils du trépas,

Dans les ténèbres

Pressent leurs pas;

Leur essaim gronde:

Ainsi, profonde,

Murmure une onde

Qu’on ne voit pas.

Ce bruit vague

Qui s’endort,

C’est la vague

Sur le bord;

C’est la plainte,

Presque éteinte,

D’une sainte

Pour un mort.

On doute

La nuit …

J’écoute: –

Tout fuit,

Tout passe

L’espace

Efface

Le bruit.

Poet Craig Raine started a new school in 1979 — “Martian poetry,” in which the ordinary is “defamiliarized” by seeing it through alien eyes:

In homes, a haunted apparatus sleeps,

that snores when you pick it up.

If the ghost cries, they carry it

to their lips and soothe it to sleep

with sounds. And yet, they wake it up

deliberately, by tickling with a finger.

Only the young are allowed to suffer

openly. Adults go to a punishment room

with water but nothing to eat.

They lock the door and suffer the noises

alone. No one is exempt

and everyone’s pain has a different smell.

At night, when all the colours die,

they hide in pairs

and read about themselves —

in colour, with their eyelids shut.

“The task of the artist at any time is uncompromisingly simple,” he said. “To discover what has not yet been done, and to do it.”

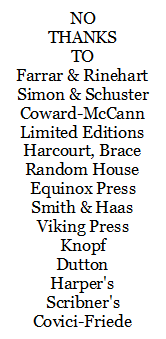

E.E. Cummings had to borrow $300 from his mother in order to publish 70 Poems, his 1935 collection of poetry. Vindictively he changed its title to No Thanks and dedicated it to the 14 publishing houses that had rejected it:

Their names form the shape of a funeral urn.

When I was a boy there was a friend of mine,

We thought ourselves warriors and grown folk swine,

Stupid old animals who never understood

And never had an impulse, and said “You must be good!”

We stank like stoats and fled like foxes,

We put cigarettes in the pillar-boxes,

Lighted cigarettes and letters all aflame–

O the surprise when the postman came!

We stole eggs and apples and made fine hay

In people’s houses when people were away,

We broke street lamps and away we ran;

Then I was a boy but now I am a man.

Now I am a man and don’t have any fun,

I hardly ever shout and never never run,

And I don’t care if he’s dead, that friend of mine,

For then I was a boy and now I am a swine.

— G.K. Chesterton

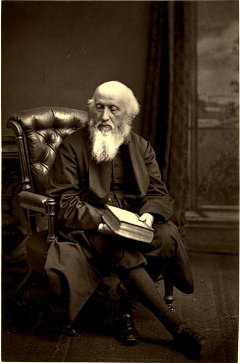

William Barnes (1801-1886) loved language too well. He had written poetry in Standard English from an early age, but in his 30s he switched to the local Dorset dialect, which he felt was more linguistically pure:

Oh! it meäde me a’most teary-ey’d,

An’ I vound I a’most could ha’ groan’d —

What! so winnèn, an’ still cast azide —

What! so lovely, an’ not to be own’d;

Oh! a God-gift a-treated wi’ scorn

Oh! a child that a squier should own;

An’ to zend her awaÿ to be born! —

Aye, to hide her where others be shown!

A philological scholar, he had come to feel that Dorset speech, true to its Anglo-Saxon origins, was the least corrupted form of English, and best suited to paint scenes of rural life. “To write in what some may deem a fast out-wearing speech-form may seem as idle as the writing of one’s name in snow on a spring day,” he wrote. “I cannot help it. It is my mother tongue, and it is to my mind the only true speech of the life that I draw.”

His contemporary admirers included Tennyson, Gerard Manley Hopkins, and Thomas Hardy, but unfortunately he was right: As Standard English increasingly outmoded his beloved dialect, his poems passed into an undeserved obscurity.

“Had he chosen to write solely in familiar English, rather than in the dialect of his native Dorsetshire, every modern anthology would be graced by the verses of William Barnes,” wrote Charles Dudley Warner. “By reason of their faithfulness to everyday life and to nature, and by their spontaneity and tenderness, his lyrics, fables, and eclogues appeal to cultivated readers as well as to the rustics whose quaint speech he made his own.”