When he wasn’t taming electromagnetism, James Clerk Maxwell wrote verse. Here’s “A Problem in Dynamics,” composed in 1854:

An inextensible heavy chain

Lies on a smooth horizontal plane,

An impulsive force is applied at A,

Required the initial motion of K.

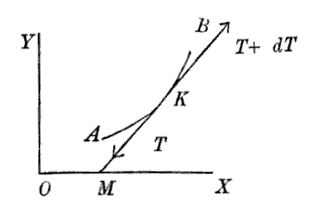

Let ds be the infinitesimal link,

Of which for the present we’ve only to think;

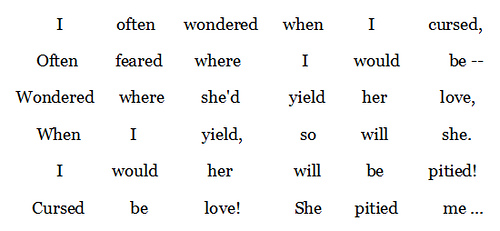

Let T be the tension, and T + dT

The same for the end that is nearest to B.

Let a be put, by a common convention,

For the angle at M ‘twixt OX and the tension;

Let Vt and Vn be ds‘s velocities,

Of which Vt along and Vn across it is;

Then Vn/Vt the tangent will equal,

Of the angle of starting worked out in the sequel.

In working the problem the first thing of course is

To equate the impressed and effectual forces.

K is tugged by two tensions, whose difference dT

Must equal the element’s mass into Vt.

Vn must be due to the force perpendicular

To ds‘s direction, which shows the particular

Advantage of using da to serve at your

Pleasure to estimate ds‘s curvature.

For Vn into mass of a unit of chain

Must equal the curvature into the strain.

Thus managing cause and effect to discriminate,

The student must fruitlessly try to eliminate,

And painfully learn, that in order to do it, he

Must find the Equation of Continuity.

The reason is this, that the tough little element,

Which the force of impulsion to beat to a jelly meant,

Was endowed with a property incomprehensible,

And was “given,” in the language of Shop, “inextensible.”

It therefore with such pertinacity odd defied

The force which the length of the chain should have modified,

That its stubborn example may possibly yet recall

These overgrown rhymes to their prosody metrical.

The condition is got by resolving again,

According to axes assumed in the plane.

If then you reduce to the tangent and normal,

You will find the equation more neat tho’ less formal.

The condition thus found after these preparations,

When duly combined with the former equations,

Will give you another, in which differentials

(When the chain forms a circle), become in essentials

No harder than those that we easily solve

In the time a T totum would take to revolve.

Now joyfully leaving ds to itself, a-

Ttend to the values of T and of a.

The chain undergoes a distorting convulsion,

Produced first at A by the force of impulsion.

In magnitude R, in direction tangential,

Equating this R to the form exponential,

Obtained for the tension when a is zero,

It will measure the tug, such a tug as the “hero

Plume-waving” experienced, tied to the chariot.

But when dragged by the heels his grim head could not carry aught,

So give a its due at the end of the chain,

And the tension ought there to be zero again.

From these two conditions we get three equations,

Which serve to determine the proper relations

Between the first impulse and each coefficient

In the form for the tension, and this is sufficient

To work out the problem, and then, if you choose,

You may turn it and twist it the Dons to amuse.