What number comes next in this series?

0, 0, 0, 0, 4, 9, 5, 1, 1, 0, 55, 55, 1, 0, 1

What number comes next in this series?

0, 0, 0, 0, 4, 9, 5, 1, 1, 0, 55, 55, 1, 0, 1

I set out to run a 26.5-mile marathon hoping to average less than 9 minutes per mile. As I run, my friends measure my time along various mile-long segments of the course. On each mile that they measure — indeed, on each mile that it’s possible to measure, starting anywhere along the course — my time is exactly 9 minutes. Yet my average for the whole marathon is less than 9 minutes per mile.

How is this possible?

How many pets do I have if all of them are dogs except two, all are cats except two, and all are fish except two?

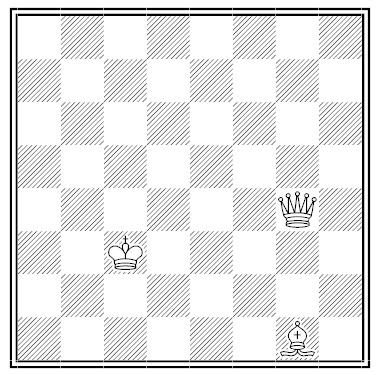

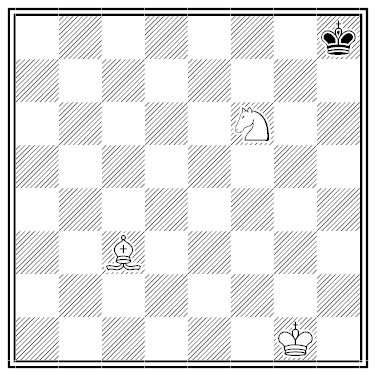

By Sam Loyd. Place the black king (a) where it can be checkmated on the move, (b) where it’s in stalemate, (c) where it’s in checkmate, and (d) where the three white pieces can’t be arranged to checkmate it.

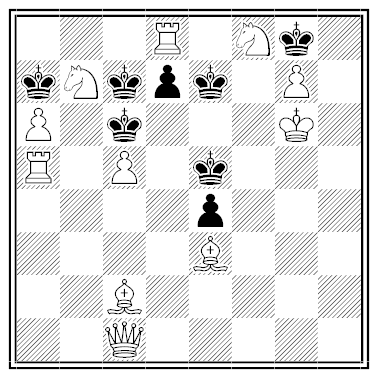

By G.A.A. Walker. White to play and checkmate all six black kings simultaneously with his second move.

A riddle by Isaac Newton:

Four people sat down at a table to play;

They play’d all that night, and some part of next day;

This one thing observ’d, that when all were seated,

Nobody play’d with them, and nobody betted;

Yet, when they got up, each was winner a guinea;

Who tells me this riddle I’m sure is no ninny.

Who are the players?

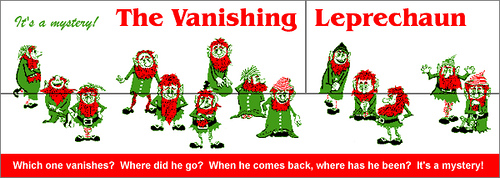

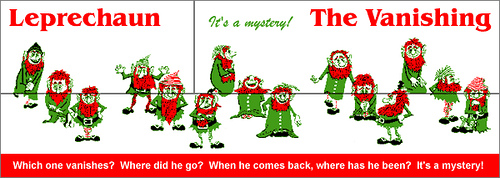

Count these leprechauns:

Now swap the two upper panels and count again:

Where has the extra one been hiding?

This puzzling verse, from a contributor named “Maude,” appeared in the Weekly Wisconsin of Sept. 29, 1888:

Perhaps the solvers are inclined to hiss,

Curling their nose up at a con like this.

Like some much abler posers I would try

A rare, uncommon puzzle to supply.

A curious acrostic here you see

Rough hewn and inartistic tho’ it be;

Still it is well to have it understood,

I could not make it plainer, if I would.

(In the second line, “con” means “contribution.”)

What are the concealed words?

One of Eduard Gufeld’s first chess coaches, A.A. Olshansky, offered him this problem:

“White to mate in half a move.”

Census Taker: How old are your three daughters?

Mrs. Smith: The product of their ages is 36, and the sum of their ages is the address on our door here.

Census Taker: (after some figuring) I’m afraid I can’t determine their ages from that …

Mrs. Smith: My eldest daughter has red hair.

Census Taker: Oh, thanks, now I know.

How old are the three girls?