Puzzles

Spirits of the Departed

A wine merchant has three sons. When he dies, he leaves them seven barrels that are full of wine, seven that are half-full, and seven that are empty. His will requires that each son receive the same number of full, half-full, and empty barrels. Can this be done?

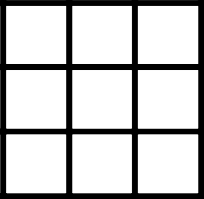

Prime Magic

In his 1976 book 100 Numerical Games, French puzzle maven Pierre Berloquin asks whether it’s possible to construct a magic square using the first nine prime numbers (here counting 1 as prime):

1 2 3 5 7 11 13 17 19

Is it?

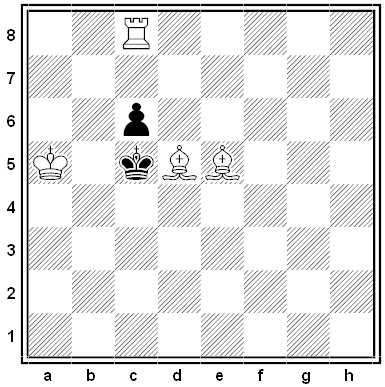

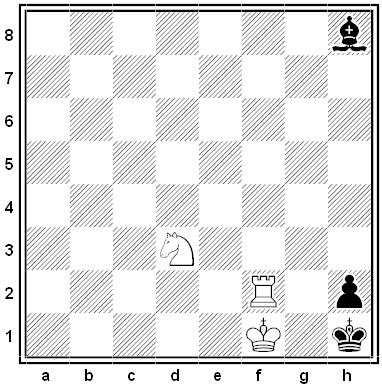

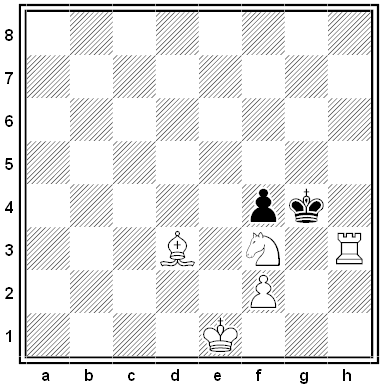

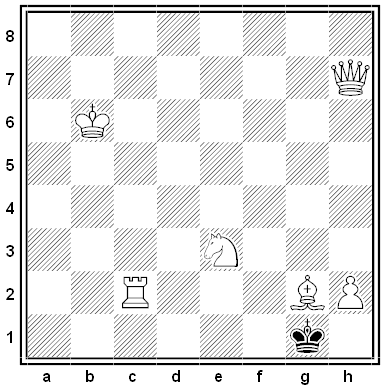

Black and White

Black and White

Podcast Episode 152: Lateral Thinking Puzzles

Here are five new lateral thinking puzzles to test your wits and stump your friends — play along with us as we try to untangle some perplexing situations using yes-or-no questions.

Black and White

In a Word

ullage

n. the amount a container lacks of being full

Given a 5-gallon jug, a 3-gallon jug, and a limitless supply of water, how can you measure out exactly 4 gallons?

The Cherries Puzzle

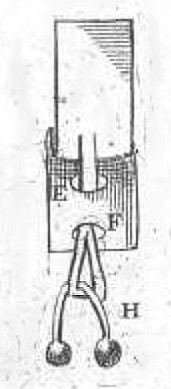

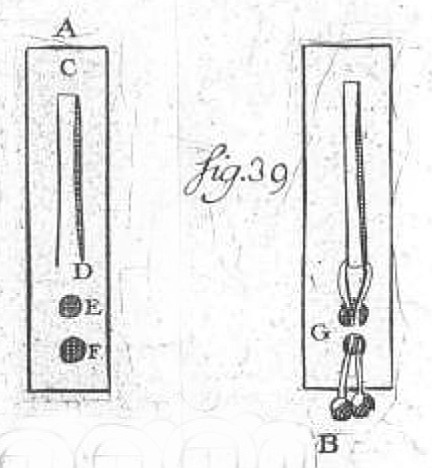

A classic puzzle from Jacques Ozanam’s Recreations Mathematiques et Physiques, 1723. Two slits (CD) and two holes (EF) are cut in a slip of paper, and a cherry stem is suspended as shown. The cherries are too large to fit through the holes. How can you free the stem and its cherries intact from the slip?

Cross Purposes

Three men, A, B, and C, are given a test in quick thinking. Each man’s forehead is marked with either a blue or a white cross, and they’re put into an empty room. None of the three can see the color of his own cross, and they aren’t allowed to communicate in any way. Each is told that he can leave the room if he either sees two white crosses or can correctly deduce the color of his own cross.

The men know each other well, and A knows he’s just a bit more alert than the others. He sees that both B and C have blue crosses, and after a moment’s thought he’s able to leave the room, having correctly named the color of his own cross. What was the color, and how did he deduce it?