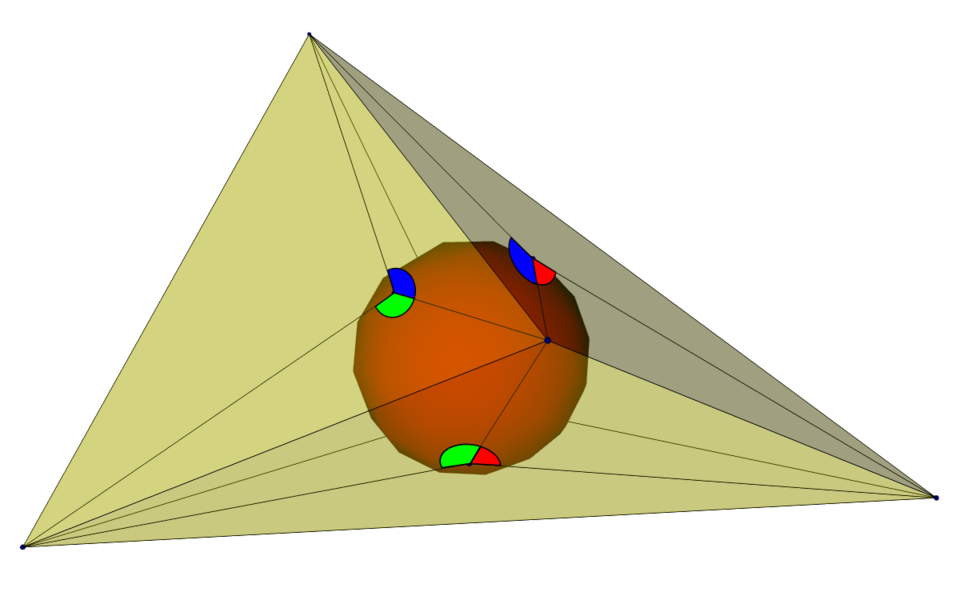

In the classic Indian rope trick, a rope rises into the sky, its end lost to view. A boy disappears up the rope, and when he fails to return the angry magician climbs up after him. Body parts fall to the ground, the magician descends and places the parts in a basket, and the boy reappears uninjured.

This is all thought to be a legend, but in 1979 mathematician J.L.G. Pinhey of The Perse Boys’ School worked out that levitating a rope is possible, at least in principle. If the top of the fakir’s rope is 1.5 × 108 meters above Earth’s surface, it will simply stand erect, its position sustained by the motion of the planet.

“Since the rope between its ends is in tension the configuration is stable, and the faqir and his boy-victim can climb it in safety. However, in order to drop the bits to earth, the pair must not climb even a quarter of the way to the top.”

(J.L.G. Pinhey, “63.12 The Indian Rope Trick,” Mathematical Gazette 63:424 [June 1979], 110-111.)