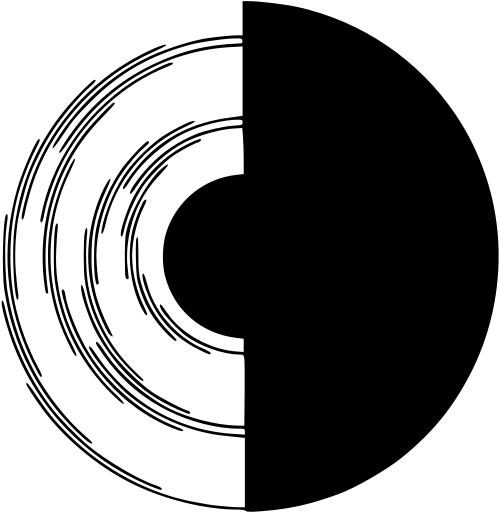

Cut out this disc, pierce it with a pencil, and spin it like a top. The colors that appear are not entirely understood; it’s thought that they arise due to the different rates of stimulation of color receptors in the retina. The effect was discovered by the French monk Benedict Prévost in 1826, and then rediscovered 12 times, most famously by the toy maker Charles E. Benham, who marketed an “artificial spectrum top” in 1894. Nature remarked on it that November: “If the direction of rotation is reversed, the order of these tints is also reversed. The cause of these appearances does not appear to have been exactly worked out.”