How to get rich using pocket handkerchiefs, from Lewis Carroll’s Sylvie and Bruno Concluded:

Here Lady Muriel returned with her father; and, after he had exchanged some friendly words with ‘Mein Herr’, and we had all been supplied with the needful ‘creature-comforts,’ the newcomer returned to the suggestive subject of Pocket-handkerchiefs.

‘You have heard of Fortunatus’s Purse, Miladi? Ah, so! Would you be surprised to hear that, with three of these leetle handkerchiefs, you shall make the Purse of Fortunatus, quite soon, quite easily?’

‘Shall I indeed?’ Lady Muriel eagerly replied, as she took a heap of them into her lap, and threaded her needle. ‘Please tell me how, Mein Herr! I’ll make one before I touch another drop of tea!’

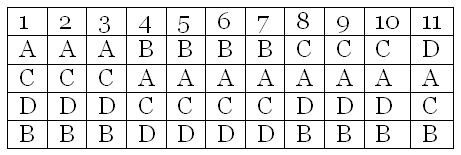

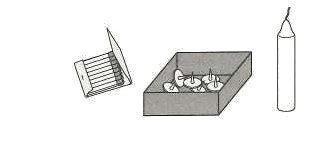

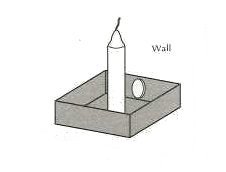

‘You shall first,’ said Mein Herr, possessing himself of two of the handkerchiefs, spreading one upon the other, and holding them up by two corners, ‘you shall first join together these upper corners, the right to the right, the left to the left; and the opening between them shall be the mouth of the Purse.’

A very few stitches sufficed to carry out this direction. ‘Now, if I sew the other three edges together,’ she suggested, ‘the bag is complete?’

‘Not so, Miladi: the lower edges shall first be joined–ah, not so!’ (as she was beginning to sew them together). ‘Turn one of them over, and join the right lower corner of the one to the left lower corner of the other, and sew the lower edges together in what you would call the wrong way.’

‘I see!’ said Lady Muriel, as she deftly executed the order. ‘And a very twisted, uncomfortable, uncanny-looking bag it makes! But the moral is a lovely one. Unlimited wealth can only be attained by doing things in the wrong way! And how are we to join up these mysterious–no, I mean this mysterious opening?’ (twisting the thing round and round with a puzzled air.) ‘Yes, it is one opening. I thought it was two, at first.’

‘You have seen the puzzle of the Paper Ring?’ Mein Herr said, addressing the Earl. ‘Where you take a slip of paper, and join its ends together, first twisting one, so as to join the upper corner of one end to the lower corner of the other?‘

‘I saw one made, only yesterday,’ the Earl replied. ‘Muriel, my child, were you not making one, to amuse those children you had to tea?’

‘Yes, I know that Puzzle,’ said Lady Muriel. ‘The Ring has only one surface, and only one edge. It’s very mysterious!’

‘The bag is just like that, isn’t it?’ I suggested. ‘Is not the outer surface of one side of it continuous with the inner surface of the other side?’

‘So it is!’ she exclaimed. ‘Only it isn’t a bag, just yet. How shall we fill up this opening, Mein Herr?’

‘Thus!’ said the old man impressively, taking the bag from her, and rising to his feet in the excitement of the explanation. ‘The edge of the opening consists of four handkerchief-edges, and you can trace it continuously, round and round the opening: down the right edge of one handkerchief, up the left edge of the other, and then down the left edge of the one, and up the right edge of the other!’

‘So you can!’ Lady Muriel murmured thoughtfully, leaning her head on her hand, and earnestly watching the old man. ‘And that proves it to be only one opening!’

She looked so strangely like a child, puzzling over a difficult lesson, and Mein Herr had become, for the moment, so strangely like the old Professor, that I felt utterly bewildered: the ‘eerie’ feeling was on me in its full force, and I felt almost impelled to say ‘Do you understand it, Sylvie?’ However I checked myself by a great effort, and let the dream (if indeed it was a dream) go on to its end.

‘Now, this third handkerchief,’ Mein Herr proceeded, ‘has also four edges, which you can trace continuously round and round: all you need do is to join its four edges to the four edges of the opening. The Purse is then complete, and its outer surface–‘

‘I see!’ Lady Muriel eagerly interrupted. ‘Its outer surface will be continuous with its inner surface! But it will take time. I’ll sew it up after tea.’ She laid aside the bag, and resumed her cup of tea. ‘But why do you call it Fortunatus’s Purse, Mein Herr?’

The dear old man beamed upon her, with a jolly smile, looking more exactly like the Professor than ever. ‘Don’t you see, my child–I should say Miladi? Whatever is inside that Purse, is outside it; and whatever is outside it, is inside it. So you have all the wealth of the world in that leetle Purse!’