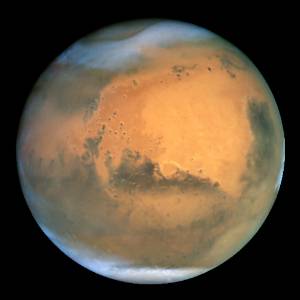

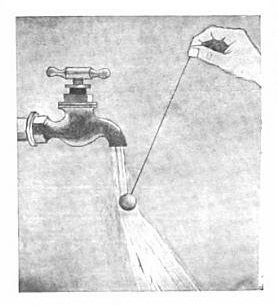

There is a legend that after Buddha died, his shadow lingered in a cave. It actually is possible for a shadow to persist without any sustaining object. Light travels at 299,792,458 meters per second in a vacuum. The moon is about 384,400,000 meters away from Earth. Hence, if the moon were instantly obliterated during a solar eclipse, its shadow would linger for more than a second on the surface of Earth. If the moon were farther away, its shadow could last several minutes. We can extrapolate to posthumous shadows that postdate their objects by millions of years. We can also speculate about an infinite past in which a shadow is sustained by a beginningless sequence of objects. As one object is destroyed, an object of the same shape and size seamlessly replaces it. This shadow antedates any object in the sequence and so refutes the principle that every shadow is caused by an object. Shadows are not dedicated dependents. Although slaves to some object or other, they can switch masters.

— Roy Sorensen, Seeing Dark Things, 2008