Four fourths exceeds three fourths by what fractional part?

“This question will usually divide a company.”

— William Frank White, A Scrap-Book of Elementary Mathematics, 1908

Four fourths exceeds three fourths by what fractional part?

“This question will usually divide a company.”

— William Frank White, A Scrap-Book of Elementary Mathematics, 1908

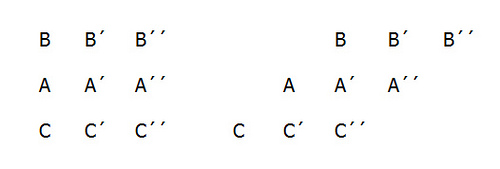

Bertrand Russell explains Zeno’s paradox of the stadium:

Let us suppose three drill-sergeants, A, A′, and A′′, standing in a row, while the two files of soldiers march past them in opposite directions. At the first moment which we consider, the three men B, B′, B′′, in one row, and the three men C, C′, C′′ in the other row, are respectively opposite to A, A′, and A′′. At the very next moment, each row has moved on, and now B and C′′ are opposite A′. When, then, did B pass C′? It must have been somewhere between the two moments which we supposed consecutive. It follows that there must be other moments between any two given moments, and therefore that there must be an infinite number of moments in any given interval of time.

In other words, if time is a series of consecutive instants, and motion means passing through consecutive points, then the Bs are passing the As at the fastest possible speed — one point per instant. How then is it that the Bs are passing the Cs at twice this rate? It seems, Aristotle noted, that “half the time is equal to its double.”

From Lee Sallows, a grid that inventories its own contents:

![]()

Suppose 10 percent of the population has a disease. Everyone is tested, and your test comes back positive. The test is 80 percent accurate. What is the chance that you have the disease?

Surprisingly, it’s little more than 30 percent. If the population is 100, then 10 people have the disease. Eight of them will get a correct positive result, 2 will get a false negative, and 18 of the remaining 90 will get a false positive. That’s 26 positives, of which only 8 are correct, or 30.8 percent.

In 1885, Cecilia Garrett Smith and a friend were experimenting with automatic writing using a primitive Ouija board on which a planchette was guided by a visiting “spirit.”

“We got all sorts of nonsense out of it, sometimes long doggerel rhymes with several verses,” but the prophecies they asked for were rarely answered. When they asked who the guiding spirit was, the planchette wrote that his name was Jim and that he had been Senior Wrangler at Cambridge. Intrigued, they asked Jim to write the equation describing the heart-shaped planchette they were using, and they received this response:

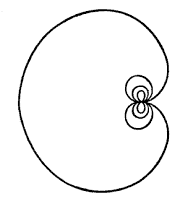

This they interpreted as ![]() , which J.W. Sharpe later graphed thus:

, which J.W. Sharpe later graphed thus:

“I am quite sure that I had never seen the curve before, and therefore the production of the equation could not have been an act of unconscious memory on my part,” Smith wrote later. “Also I most certainly did not know enough mathematics to know how to form an equation which would represent such a curve, or to know even of what type the equation must be.”

One wonders what Jim thought of all this. They never got any further math out of him.

If there will be a sea battle tomorrow, then that fact is true today and has always been true. Our future is thus inevitable. What freedom is left to us?

On the other hand, if statements about the future are neither true nor false today, then how can God have perfect foreknowledge of the future?

A favorite problem of Lewis Carroll involves a customer trying to complete a purchase using pre-decimal currency. He wants to buy 7s. 3d. worth of goods, but he has only a half-sovereign (10s.), a florin (2s.), and a sixpence. The shopkeeper can’t give him change, as he himself has only a crown (5s.), a shilling, and a penny. As they’re puzzling over this a friend enters the shop with a double-florin (4s.), a half-crown (2s. 6d.), a fourpenny-bit, and a threepenny-bit. Can the three of them negotiate the transaction?

Happily, they can. They pool their money on the counter, and the shopkeeper takes the half-sovereign, the sixpence, the half-crown, and the fourpenny-bit; the customer takes the double-florin, the shilling, and threepenny-bit as change; and the friend takes the florin, the crown, and the penny.

“There are other combinations,” writes John Fisher in The Magic of Lewis Carroll, “but this is the most logistically pleasing, as it will be seen that not one of the three persons retains any one of his own coins.”

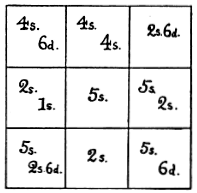

Related: From Henry Dudeney, a magic square:

(Strand, December 1896)