3435= 33 + 44 + 33 + 55

Science & Math

Stops and Starts

Charade sentences devised by Howard Bergerson:

FLAMINGO: PALE, SCENTING A LATENT SHARK! =

FLAMING, OPALESCENT IN GALA TENTS — HARK!

NO! UNCLE-AND-AUNTLESS BE, AS TIES DENY OUR END.

NO UNCLEAN, DAUNTLESS BEASTIES’ DEN YOU REND.

HISS, CARESS PURSUIT, OR ASTOUND, O ROC, O COBRAS!

HIS SCARES SPUR SUITOR, AS TO UNDO ROCOCO BRAS.

HA! THOU TRAGEDY INGRATE, DWELL ON, SUPERB OLD STAG IN GLOOM =

HATH OUTRAGE, DYING, RATED WELL? ON SUPER-BOLD STAGING LOOM!

In the same spirit: 1! 10! 22! 1! = 11! 0! 2! 21!

Faith and Reason

Jean Buridan presented a logical proof of the existence of God:

- God exists.

- Neither of these sentences is true.

The two statements can be reconciled only if God exists.

But see Cloudy, Kangaroo Court, and Powerless.

Blowing in the Wind

A dust storm approaches Spearman, Texas, April 1935. Vance Johnson, a resident of western Kansas in the 1930s, described similar storms there:

The darkness was dust. The windows turned solid pitch; even flower boxes six inches beyond the pane were shut from view. … Dust sifted into houses, through cracks around the doors and windows — so thick even in well-built homes a man in a chair across the room became a blurred outline. Sparks flew between pieces of metal, and men got a shock when they touched the plumbing. It hurt to breath[e], but a damp cloth held over mouth and nose helped for a while. Food on tables freshly set for dinner ruined. Milk turned black. Bed, rugs, furniture, clothes in the closets, and food in the refrigerator were covered with a film of dust. Its acrid odor came out of pillows for days afterward.

During a dust storm in January 1895, J.C. Neal of Oklahoma A&M College reported “flashes of light that apparently started from no particular place, but prevaded [sic] the dust everywhere. As long as the wind blew, till about 2 a.m., January 21, this free lightning was everywhere but there was no noise whatever. It was a silent electrical storm.”

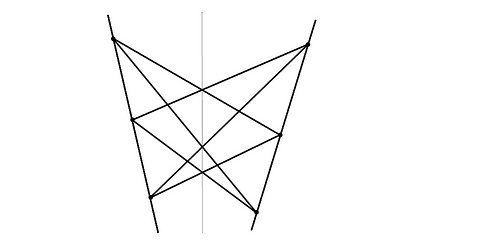

Inside Straight

Draw any two lines, pick three points on each, and lace them all together like so:

The crossings of the laces will always form a straight line.

The Value of Tardiness

One day in 1939, Berkeley doctoral candidate George Dantzig arrived late for a statistics class taught by Jerzy Neyman. He copied down the two problems on the blackboard and turned them in a few days later, apologizing for the delay — he’d found them unusually difficult. Distracted, Neyman told him to leave his homework on the desk.

On a Sunday morning six weeks later, Neyman knocked on Dantzig’s door. The problems that Dantzig had assumed were homework were actually unproved statistical theorems that Neyman had been discussing with the class — and Dantzig had proved both of them. Both were eventually published, with Dantzig as coauthor.

“When I began to worry about a thesis topic,” he recalled later, “Neyman just shrugged and told me to wrap the two problems in a binder and he would accept them as my thesis.”

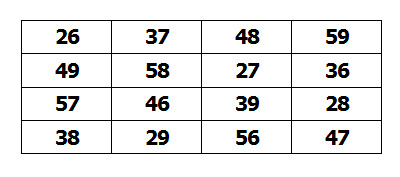

An Alphamagic Square

Each row and column in this magic square totals 170.

If you update the contents of each cell by spelling out its number in English, counting the letters and recording the result (26 = TWENTY-SIX = nine letters = 9), you’ll produce another magic square.

Inventory Trouble

- This sentence contains four words.

- This sentence contains five words.

- Exactly one sentence in this list is true.

Unquote

“Sometimes I think we’re alone in the universe, and sometimes I think we’re not. In either case the idea is quite staggering.” — Arthur C. Clarke

Chisholm’s Paradox

Adam and Noah exist here now. Adam lives to be 930, Noah 950. We can imagine a possible world in which they swap ages and yet retain their essential identities. But we can also imagine a further world in which they swap ages and names; another in which they swap ages, names, and hat sizes; and finally a world in which Adam and Noah have swapped all their qualitative properties.

Now isn’t Adam in our world identical with Noah in the other world? For how are they distinct? If a thing can retain its essential identity when a single property is changed, then, writes Willard Van Orman Quine, “You can change anything to anything by easy stages through some connecting series of possible worlds.”

See Spare Parts.