49 + 79 + 29 + 39 + 39 + 59 + 99 + 79 + 59 = 472335975

Science & Math

No Vacancy

“What happens to the hole when the cheese is gone?” — Bertolt Brecht

The Unrepentant Liar

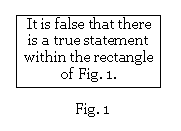

“According to [Bertrand] Russell’s treatment the sentence within the rectangle of Fig. 1 is meaningless, and may be called a pseudo-statement, because it is a version of the liar-paradox. But Russell’s treatment is unsatisfactory because it resolves the original paradox at the price of a new one. For, if the sentence of Fig. 1 is meaningless we must admit, since we observe that there are no other sentences within the rectangle, that it is false that there is a genuine or meaningful statement within the rectangle of Fig. 1. And, if there is no statement within the rectangle of Fig. 1 then it is false that there is a true statement within the rectangle of Fig. 1. The italicized part of the preceding sentence will be recognized as identical with (even if a different token of) the sentence within the rectangle of Fig. 1. And since the italicized sentence is true, and therefore a meaningful statement, the sentence within the rectangle is not a pseudo-statement either. Thus, if the sentence in question is meaningless, then it is meaningful and vice versa.”

— A.P. Ushenko, “A Note on the Liar Paradox,” Mind, October 1955

Faith No More

Kurt Gödel composed an ontological proof of God’s existence:

Axiom 1. A property is positive if and only if its negation is negative.

Axiom 2. A property is positive if it necessarily contains a positive property.

Theorem 1. A positive property is logically consistent (that is,

possibly it has an existence).

Definition. Something is God-like if and only if it possesses all positive properties.

Axiom 3. Being God-like is a positive property.

Axiom 4. Being a positive property is logical and hence necessary.

Definition. A property P is the essence of x if and only if x has the property P and P is necessarily minimal.

Theorem 2. If x is God-like, then being God-like is the essence of x.

Definition. x necessarily exists if it has an essential property.

Axiom 5. Being necessarily existent is God-like.

Theorem 3. Necessarily there is some x such that x is God-like.

“I am convinced of the afterlife, independent of theology,” he once wrote. “If the world is rationally constructed, there must be an afterlife.”

Hintikka’s Paradox

(1) If a thing can’t be done without something wrong being done, then the thing itself is wrong.

(2) If X is impossible and Y is wrong, then I can’t do both X and Y, and I can’t do X but not Y.

But if Y is wrong and doing X-but-not-Y is impossible, then by (1) it’s wrong to do X.

Hence if it’s impossible to do a thing, then it’s wrong to do it.

Oaks and Acorns

Each of these pairs of numbers contains the 10 digits:

57321 60984

35172 60984

58413 96702

59403 76182

Square any one of them and it will grow into its own 10-digit pandigital number.

In the Dark

“A universe simple enough to be understood is too simple to produce a mind capable of understanding it.” — Cambridge cosmologist John Barrow

Homework

One day while teaching a class at Yale, Shizuo Kakutani wrote a lemma on the blackboard and remarked that the proof was obvious. A student timidly raised his hand and said that it wasn’t obvious to him. Kakutani stared at the lemma for some moments and realized that he couldn’t prove it himself. He apologized and said he would report back at the next class meeting.

After class he went straight to his office and worked for some time further on the proof. Still unsuccessful, he skipped lunch, went to the library, and tracked down the original paper. It stated the lemma clearly but left the proof as an “exercise for the reader.”

The author was Shizuo Kakutani.

Who’s On First?

Stigler’s Law of Eponymy states that “no scientific discovery is named after its original discoverer.” Examples:

- Arabic numerals were invented in India.

- Darwin lists 18 predecessors who had advanced the idea of evolution by natural selection.

- Freeman Dyson credited the idea of the Dyson sphere to Olaf Stapledon.

- Salmonella was discovered by Theobald Smith but named after Daniel Elmer Salmon.

- Copernicus propounded Gresham’s Law.

- Pell’s equation was first solved by William Brouncker.

- Euler’s number was discovered by Jacob Bernoulli.

- The Gaussian distribution was introduced by Abraham de Moivre.

- The Mandelbrot set was discovered by Pierre Fatou and Gaston Julia.

University of Chicago statistics professor Stephen Stigler advanced the idea in 1980.

Delightfully, he attributes it to Robert Merton.

Infallible

[Bertrand] Russell is reputed at a dinner party once to have said, ‘Oh, it is useless talking about inconsistent things, from an inconsistent proposition you can prove anything you like.’ Well, it is very easy to show this by mathematical means. But, as usual, Russell was much cleverer than this. Somebody at the dinner table said, ‘Oh, come on!’ He said, ‘Well, name an inconsistent proposition,’ and the man said, ‘Well, what shall we say, 2 = 1.’ ‘All right,’ said Russell, ‘what do you want me to prove?’ The man said, ‘I want you to prove that you are the pope.’ ‘Why,’ said Russell, ‘the pope and I are two, but two equals one, therefore the pope and I are one.’

— Jacob Bronowski, The Origins of Knowledge and Imagination, 1979