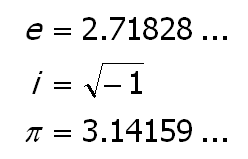

You know these numbers:

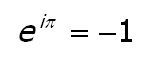

On the surface they appear unrelated. e is the base of natural logarithms, i is imaginary, π concerns circles. But, amazingly:

Harvard mathematician Benjamin Peirce told a class, “It is absolutely paradoxical; we cannot understand it, and we don’t know what it means, but we have proved it, and therefore we know it must be the truth.”