In the decimal expansion for pi, the digits 16470 appear in position 16,470.

And the digits 44899 appear in position 44,899.

In the decimal expansion for pi, the digits 16470 appear in position 16,470.

And the digits 44899 appear in position 44,899.

37 = 32 + 72 – 3 × 7 = (33 + 73)/(3 + 7)

In 1961, astronaut Gus Grissom nearly drowned after a splashdown when his Mercury capsule opened prematurely. He recommended making the hatch more secure.

Eight years later he died when Apollo 1 caught fire. The hatch had prevented his escape.

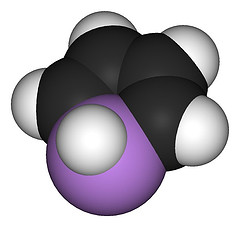

This compound, C4H5As, is known as arsole.

When it’s fused to a benzene ring, it’s called benzarsole.

No, I’m not above pointing that out.

371 = 33 + 73 + 13

5882 + 23532 = 5882353

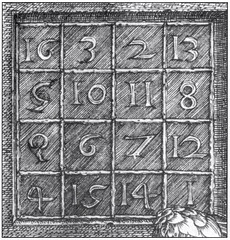

Albrecht Dürer’s Melencolia I might brood about thwarted creativity, but it contains one of the most brilliant magic squares in all of European art.

You can reach the sum of 34 by adding the numbers in any row, column, diagonal, or quadrant; the four center squares; the four corner squares; the four numbers clockwise from the corners; or the four counterclockwise.

As a bonus, the two numbers in the middle of the bottom row give the date of the engraving: 1514.

0588235294117647 × 1 = 0588235294117647

0588235294117647 × 8 = 4705882352941176

0588235294117647 × 3 = 1764705882352941

0588235294117647 × 2 = 1176470588235294

0588235294117647 × 7 = 4117647058823529

0588235294117647 × 5 = 2941176470588235

0588235294117647 × 9 = 5294117647058823

0588235294117647 × 6 = 3529411764705882

0588235294117647 × 4 = 2352941176470588

Victoria Crater, on Mars. The black dot on the rim, at about the 10 o’clock position, is the Mars rover Opportunity. Expected to fail after 90 days, it has been exploring faithfully for more than three years.

n2 – n + 41 produces prime numbers for all integers from 0 to 40 — but it fails when n equals 41.