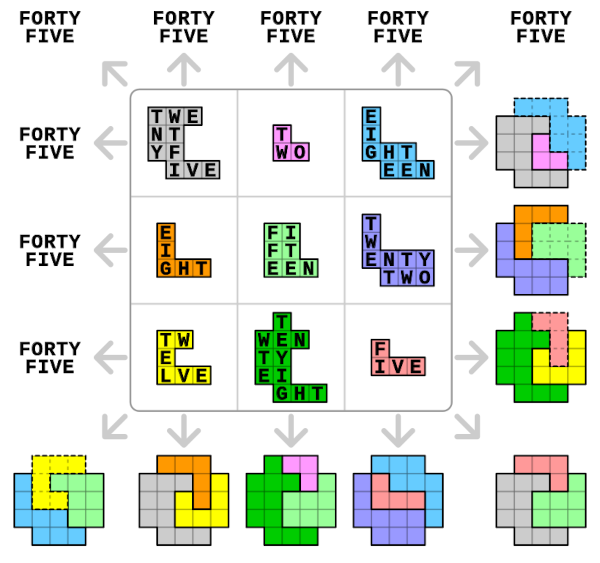

A stunning geometric alphamagic square by Lee Sallows. The 3 × 3 grid is a familiar magic square in which each number is spelled out: The first cell contains the number 25, the second 2, and so on. Interpreted in this way, each row, column, and long diagonal sums to 45.

But there’s more: The English name of the number in each cell has been arranged onto a distinctive tile, such that the three tiles in any row, column, or long diagonal can be combined to form the same 21-cell figure, as shown. (Shapes with dotted outlines have been turned over.)

And yet more: Count the number of letters in each of the number names (or, equivalently, count the number of cells that make up each tile). So, for example, TWENTY-FIVE has 10 letters, so replace the TWENTYFIVE tile with the number 10. Similarly, replace TWO with 3, EIGHTEEN with 8, and so on. This produces another magic square:

10 3 8 5 7 9 6 11 4

Each row, column, and long diagonal totals 21.