1. An object’s motion can be described by derivatives and integrals of displacement. The first few derivatives — position, velocity, and acceleration — are familiar, but the succeeding ones have pleasing names: jerk, jounce (also known as snap), crackle, pop, lock, and drop.

The integrals of displacement are absement, absity, abseleration, abserk, and absounce. More here. (Thanks, Colin.)

2. The quarks now known as “bottom” and “top” were sometimes referred to initially as “beauty” and “truth.” Collider experiments designed to produce large numbers of B mesons are sometimes called “beauty factories.” (Thanks, Jackson.)

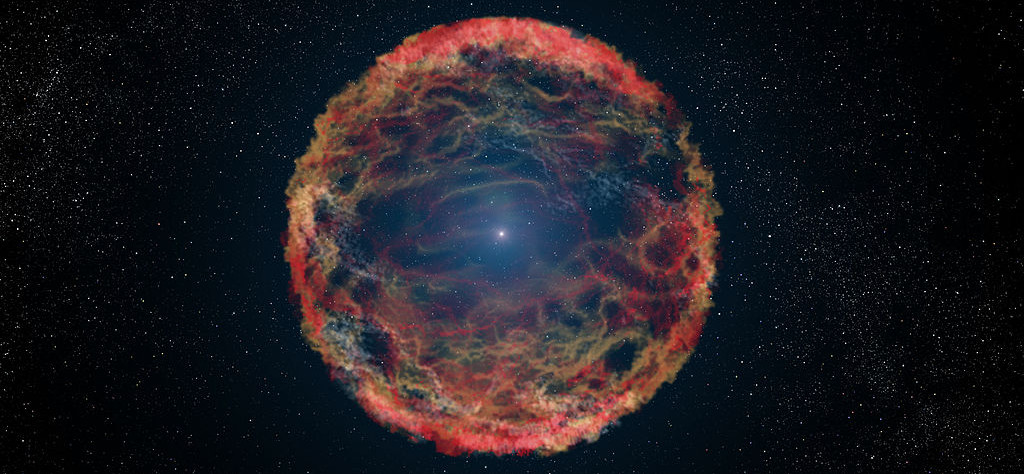

3. Reader Nick Ortenzio found this unexpectedly poignant quote in the Wikipedia article on false vacuum, from a paper in which Sidney Coleman and Frank De Luccia consider the prospect that our universe exists in an unstable bubble that might wink into a new state and annihilate us:

The possibility that we are living in a false vacuum has never been a cheering one to contemplate. Vacuum decay is the ultimate ecological catastrophe; in the new vacuum there are new constants of nature; after vacuum decay, not only is life as we know it impossible, so is chemistry as we know it. However, one could always draw stoic comfort from the possibility that perhaps in the course of time the new vacuum would sustain, if not life as we know it, at least some structures capable of knowing joy. This possibility has now been eliminated.