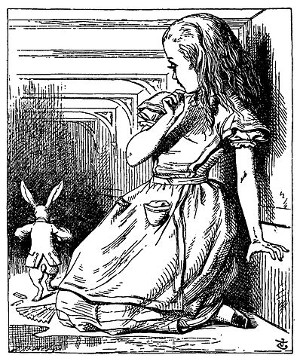

“I’m sure I’m not Ada, for her hair goes in such long ringlets, and mine doesn’t go in ringlets at all; and I’m sure I can’t be Mabel, for I know all sorts of things, and she, oh! she knows such a very little! Besides, she’s she, and I’m I, and — oh dear, how puzzling it all is! I’ll try if I know all the things I used to know. Let me see: four times five is twelve, and four times six is thirteen, and four times seven is — oh dear! I shall never get to twenty at that rate!”

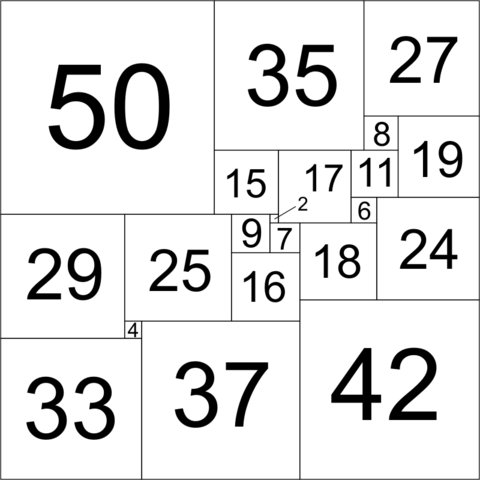

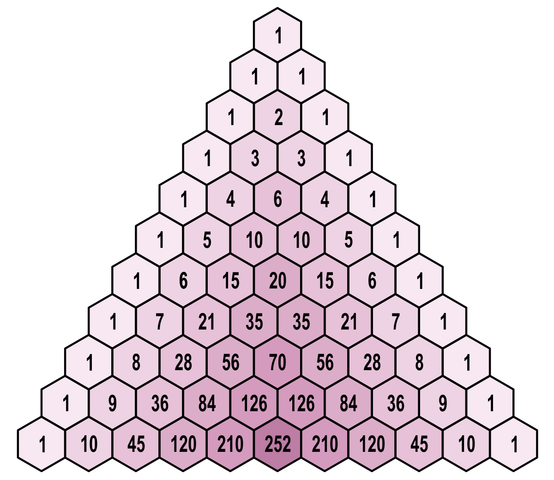

So frets Alice outside the garden in Wonderland. Is the math only nonsense? In his book The White Knight, Alexander L. Taylor finds one way to make sense of it: In base 18, 4 times 5 actually is 12. And in base 21, 4 times 6 is 13. Continuing this pattern:

4 times 7 is 14 in base 24

4 times 8 is 15 in base 27

4 times 9 is 16 in base 30

4 times 10 is 17 in base 33

4 times 11 is 18 in base 36

4 times 12 is 19 in base 39

And here it becomes clear why Alice will never get to 20: 4 times 13 doesn’t equal 20 in base 42, as the pattern at first seems to suggest, but rather 1X, where X is whatever symbol is adopted for 10.

Did Lewis Carroll have this in mind when he contrived the story for Alice? Perhaps? In The Magic of Lewis Carroll, John Fisher writes, “It is hard … not to accept Taylor’s theory that Carroll was anxious to make the most of two worlds; the problem as interpreted by Taylor interested him, and although it wouldn’t interest Alice there was no reason why he shouldn’t use it to entertain her on the level of nonsense. It is even more difficult to suppose that he, a mathematical don, inserted the puzzle in the book without realising it.”

In the Winter 1971 edition of Jabberwocky, the quarterly publication of the Lewis Carroll Society, Taylor wrote, “If you find a watch in the Sahara Desert you don’t think it grew there. In this case we know who put it there, so if he didn’t record it that tells us something about his recording habits. It doesn’t tell us that the mathematical puzzle isn’t a mathematical puzzle.”