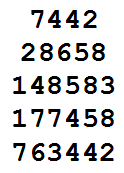

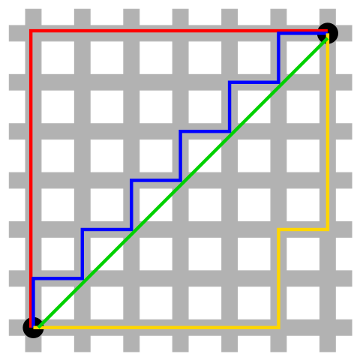

What’s the shortest distance between the points in the lower left and upper right? In our familiar Euclidean geometry, it’s the green line. But in taxicab geometry, an intriguing variant devised by Hermann Minkowski in the 19th century, distance is reckoned as the sum of the absolute differences of Cartesian coordinates — basically the distance that a taxicab would drive if this were a city grid. In that case, the shortest distance between the two points is 12, and it’s shown equally well by the red, blue, and yellow lines. Any of these routes will cover the same “distance” in taking you from one point to the other.

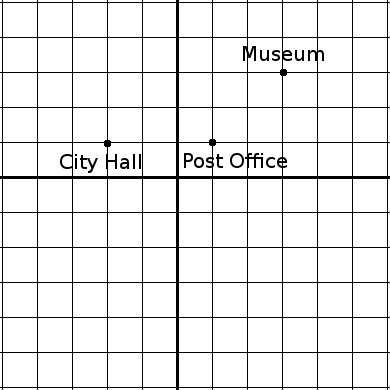

This way of considering things is intriguing in the abstract, but it has some practical value as well. “Taxicab geometry is a more useful model of urban geography than is Euclidean geometry,” writes Eugene F. Krause in Taxicab Geometry. “Only a pigeon would benefit from the knowledge that the Euclidean distance from the Post Office to the Museum [below] is blocks while the Euclidean distance from the Post Office to the City Hall is

blocks. This information is worse than useless for a person who is constrained to travel along streets or sidewalks. For people, taxicab distance is the ‘real’ distance. It is not true, for people, that the Museum is ‘closer’ to the Post Office than the City Hall is. In fact, just the opposite is true.”