“King James said to the fly, Have I three kingdoms, and thou must needs fly into my eye?” — John Selden

“The autocrat of Russia possesses more power than any other man in the earth, but he cannot stop a sneeze.” — Mark Twain

“King James said to the fly, Have I three kingdoms, and thou must needs fly into my eye?” — John Selden

“The autocrat of Russia possesses more power than any other man in the earth, but he cannot stop a sneeze.” — Mark Twain

Why do people in bygone days wear such gloomy expressions? In the 16th and 17th centuries, smiling wasn’t encouraged in part because of poor dental hygiene. Louis XIV had no teeth, and the Mona Lisa may have been trying to hide gaps or stains in her smile.

Beyond the dental challenge, broad smiles and open laughter were often actively criticized, seen as reflecting a distressing lack of emotional control. Upper-class manners insisted that a boisterous laugh was a sign of poor breeding, really no better than a yawn or a fart. A French Catholic writer argued, in 1703, ‘God would not have given humans lips if He had wanted the teeth to be on open display.’ Children might smile, to be sure, but an adult should have learned to know better.

Fashionable audiences disdained laughing aloud — Molière said that this goal was not to entertain but to “correct the faults of men.” And in Protestant countries people sought to “walk humbly” in the sight of God — one writer commented that in his view, the Almighty “allowed of no joy or pleasure, but of a kind of melancholy demeanor or austerity.” This finally changed with the Enlightenment — John Byrom wrote in 1728, “It was the best thing one could do to be always cheerful.”

(Peter N. Stearns, Happiness in World History, 2020.)

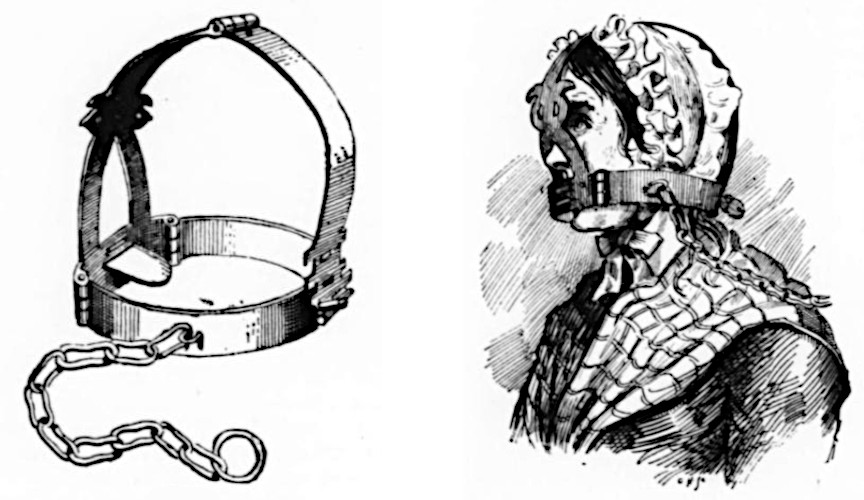

The brank consisted of a kind of crown or framework of iron, which was locked upon the head of the delinquent. It was armed in front with a gag, plate, point or knife of the same metal, which was fitted in such a manner as to be inserted in the scold’s mouth so as to prevent her moving her tongue; or, more cruel still, it was so placed that if she did move it, or attempt to speak, her tongue was cruelly lacerated, and her sufferings intensified. With this cage upon her head, and with the gag pressed and locked upon the tongue, the poor creature was paraded through the streets, led by the beadle or constable, or else she was chained to the pillory or market cross to be the object of scorn and derision, and to be subjected to all the insults and degradations that local loungers could invent.

— “Muzzles for Ladies,” Strand, November 1894

For myself, I must say that I find [Edward] Lear funniest when he is least arbitrary and when a touch of burlesque or perverted logic makes its appearance. … While the Pobble was in the water some unidentified creatures came and ate his toes off, and when he got home his aunt remarked:

‘It’s a fact the whole world knows,

That Pobbles are happier without their toes,’which once again is funny because it has a meaning, and one might even say a political significance. For the whole theory of authoritarian governments is summed up in the statement that Pobbles were happier without their toes.

— George Orwell, “Nonsense Poetry,” 1945

A Weak Man going down-hill met a Strong Man going up, and said:

‘I take this direction because it requires less exertion, not from choice. I pray you, sir, assist me to regain the summit.’

‘Gladly,’ said the Strong Man, his face illuminated with the glory of his thought. ‘I have always considered my strength a sacred gift in trust for my fellow-men. I will take you up with me. Go behind me and push.’

— Ambrose Bierce, Fantastic Fables, 1899

Rules of the Anti-Flirt Club, active in the early 1920s in Washington, D.C.:

The club’s main purpose was to protect women from men who abused “the precedent established during the war by offering to take young lady pedestrians in their cars,” according to an article in the Washington Post. Helen Brown, secretary of the 10-member club, warned that men “don’t all tender their invitations to save the girls a walk.”

In Jewish Bankers and the Holy See (2012), León Poliakov cites a joke current in 12th-century ghettos to justify usury between Jews.

“It consisted, it is said, of reciting Deuteronomy 23:20 in interrogative tones to make it mean the opposite of its obvious sense:

“‘Unto a foreigner thou mayest lend upon usury; but unto thy brother thou shalt not lend upon usury?'”

Advice sent by Philip Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield (1694–1773), to his son Philip on how to attain success in the world:

“I wish to God,” he wrote in 1750, “that you had as much pleasure in following my advice, as I have in giving it to you.”

(From Letters to His Son on the Art of Becoming a Man of the World and a Gentleman, 1774.)

My Aunt Maria asked me to read the life of Dr. Chalmers, which, however, I did not promise to do. Yesterday, Sunday, she was heard through the partition shouting to my Aunt Jane, who is deaf, ‘Think of it! He stood half an hour today to hear the frogs croak, and he wouldn’t read the life of Chalmers.’

— Thoreau, journal, March 28, 1853

In a democracy, a voter might reasonably choose to vote in their own interests or to vote for their idea of the common good. This divergence can spell trouble. Suppose voters are choosing between two options, A and B. A is in the interests of 40 percent of the electorate, and B is in the interests of the remaining 60 percent. Now suppose that 80 percent of voters believe that B is for the common good, and 20 percent believe that A is for the common good. And suppose that these beliefs are independent of interests — that is, believers in A and believers in B are spread evenly through the electorate. Finally, suppose that voters for whom A is in their interests vote according to interest while voters for whom B is in their interests vote according to their idea of the common good.

The result is that 52 percent of voters (all A-interest voters and 20 percent of B-interest voters) will vote for A, which wins the day, “even though it is in the minority interest, and believed by just 20% of the population to be in the common good,” notes philosopher Jonathan Wolff. The scenario in this example may be unlikely, but “the key assumption is that morally motivated individuals can make a mistake about what morality requires. … [W]e cannot rely on any assurances that democratic decision-making reveals either the majority interest or the common good.”

(Jonathan Wolff, “Democratic Voting and the Mixed-Motivation Problem,” Analysis 54:4 [October 1994], 193-196.)