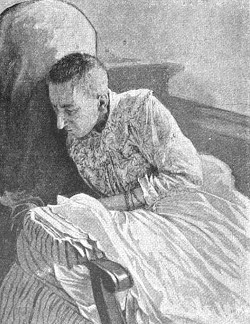

In May 1901, the attorney general of Paris received an anonymous letter. It read, “I have the honor to inform you of an exceptionally serious occurrence. I speak of a spinster who is locked up in Madame Monnier’s house, half-starved and living on a putrid litter for the past twenty-five years — in a word, in her own filth.”

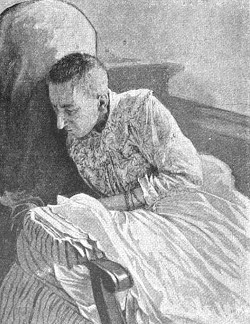

When police investigated, they found in Monnier’s attic a 52-year-old woman who weighed barely 25 kilograms. One policeman described the scene: “The unfortunate woman was lying completely naked on a rotten straw mattress. All around her was formed a sort of crust made from excrement, fragments of meat, vegetables, fish, and rotten bread. … We also saw oyster shells, and bugs running across Mademoiselle Monnier’s bed. The air was so unbreathable, the odor given off by the room was so rank, that it was impossible for us to stay any longer to proceed with our investigation.”

In 1874, when Blanche was 25, her mother Louise had locked her away to prevent her marrying a “penniless lawyer,” and for 25 years she and Blanche’s brother had pretended that she had disappeared. Louise was arrested but died shortly afterward; the brother was convicted but acquitted on appeal. Blanche was admitted to a psychiatric hospital but died in 1913. The identity of the letter writer who revealed all this was never discovered.