During the Jim Crow era, it was difficult and dangerous for African-Americans to travel — they were routinely refused even basic amenities such as food and lodging. Civil rights leader (and now Georgia congressman) John Lewis remembered a family trip in 1951:

There would be no restaurant for us to stop at until we were well out of the South, so we took our restaurant right in the car with us. … Stopping for gas and to use the bathroom took careful planning. Uncle Otis had made this trip before, and he knew which places along the way offered ‘colored’ bathrooms and which were better just to pass on by. Our map was marked and our route was planned that way, by the distances between service stations where it would be safe for us to stop.

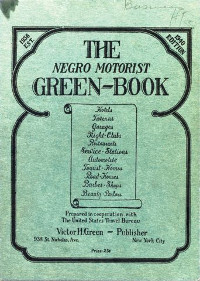

Accordingly New York mail carrier Victor H. Green began to publish The Negro Motorist Green Book, a guide “to give the Negro traveler information that will keep him from running into difficulties, embarrassments and to make his trip more enjoyable.” Green paid his readers to contribute reports of road conditions, sites of interest, and information about their travel experiences. Julian Bond later recalled:

You think about the things that most travelers take for granted, or most people today take for granted. If I go to New York City and want a hair cut, it’s pretty easy for me to find a place where that can happen, but it wasn’t easy then. White barbers would not cut black peoples’ hair. White beauty parlors would not take black women as customers — hotels and so on, down the line. You needed the Green Book to tell you where you can go without having doors slammed in your face.

The book was published annually nationwide from 1937 to 1964. The New York Public Library has the full collection.

08/25/2017 UPDATE: Using structured data extracted from the books’ listings, NYPL Labs’ Brian Foo created Navigating the Green Book, an interface that lets you map a trip between two points based on either the 1947 or the 1956 edition. The program looks for a restaurant every 250 miles and lodging every 750 miles. (Thanks, Sara.)