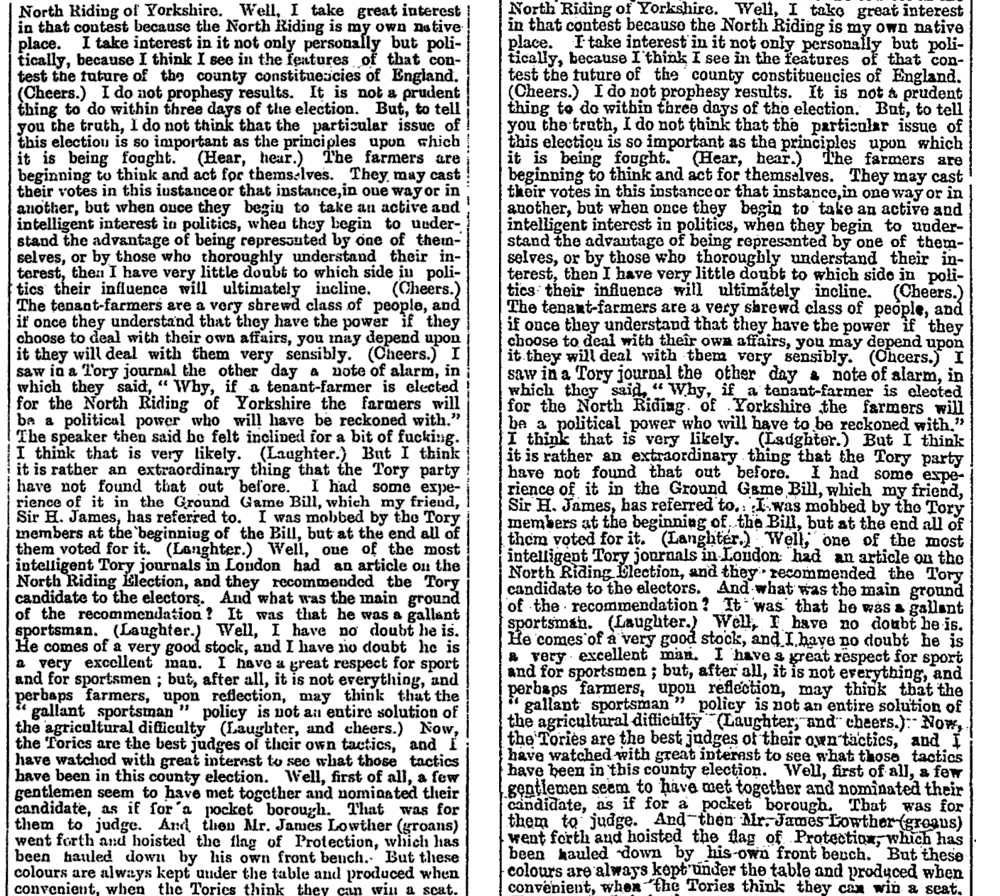

In 1895, when a Chicago landowner failed to pay his taxes, a bidder acquired a claim to the east one-vigintillionth part of the lot. The insurance company tried to foreclose, arguing that the owner had allowed a cloud to come on the title by the loss of this small fraction. But the county court held that a vigintillionth (1/1000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000) was practically nothing, as “its width would be so fine that the most powerful magnifying glass ever made could not discover it: it would be utterly incapable of physical possession.” In a little rhapsody, the Northwestern Law Review agreed:

If the surface of the earth were rolled out flat and a vigintillionth sold off the east side and sold to pay the taxes of the owner thereof, the purchaser at the tax sale would get a strip about 500 quin-decillionths of an inch wide. Hardly large enough for even a Pingree potato patch.

If the holder of the fee simple title to the section of space between the earth and the sun, (taken at 93,000,000 miles), should be unfortunate enough to be sold out to the tax buyer, he would, if he failed to redeem, lose title to a strip along one side of his holding, (say next the sun), some 140 qual decillionths of an inch in width.

Or, if the ‘unknown owner’ of the space between here and the nearest fixed star, (Alpha Centauri), something like twenty million millions of miles from the Northeast corner of Randolph and State Sts. should be unfortunate in his real estate venture and fall into the greedy hands of the tax buyer, he would have to yield up dominion over a strip on the East side of his subdivision some 645 dio decellionths of an inch across.

So did the Economist. But a higher court reversed the ruling, arguing that although a vigintillionth of the property “could not be appreciated by the senses, it is recognizable by the mind,” and that its existence left the rest of the property inaccessible by the street on the east side.

This must be some odd trend of American law in the 1890s — in his Strangest Cases on Record (1940), John Allison Duncan mentions another such case in Arapahoe County, Colorado. He includes a photograph of the certificate of purchase.