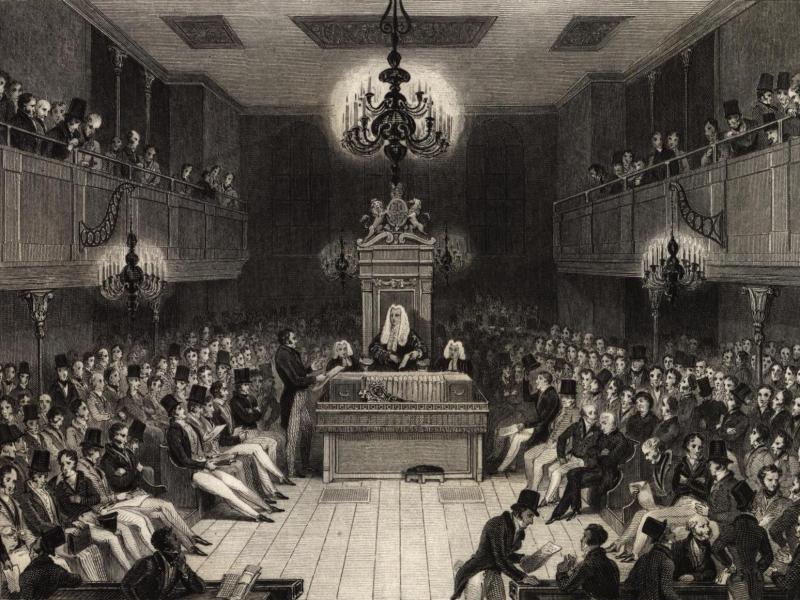

Hat-wearing rules in the British House of Commons, 1900:

At all times remove your hat on entering the House and put it on upon taking your seat; remove it again on rising for whatever purpose. If the MP asks a Question he will stand with his hat off and he may receive the Minister’s answer seated and with his hat on. If, on a Division, he should have to challenge the ruling of the Chair, he will sit and put his hat on. If he wishes to address the Speaker on a Point of Order not connected with a Division, he will do so standing with his hat off. When he leaves the Chamber to participate in a Division he will take his hat off, but will vote with it on.

As the century wore on hats grew rare, but technically a Member still had to be properly “seated and covered” to raise a Point of Order during a Division. Accordingly the Serjeant at Arms began to keep two collapsible opera hats for the purpose. In Great Political Eccentrics, Neil Hamilton writes, “Often, several Members wished to raise Points of Order in rapid succession, causing the opera hat to race around the Chamber like a relay baton.”

During one hot spell in July 1893, T.P. O’Connor called Joseph Chamberlain a Judas and a brawl broke out. In the words of Chamberlain’s biographer, “one could see the teeth set, the eyes flashing, faces aflame with wrath and a thicket of closed fists beating about in wild confusion.”

In the midst of this the Serjeant at Arms appeared and addressed himself to a Member standing below the gangway. “I beg your pardon,” he said, “but you’re standing up with your hat on, which you know is a breach of order.”

09/15/2016 UPDATE: The tradition lives on in the Australian House of Representatives: Just two weeks ago MP Christopher Pyne, stuck without a tophat, held a sheet of paper over his head while speaking to Labor’s Tony Burke. Members are required to “speak covered” when the Speaker has called a division.