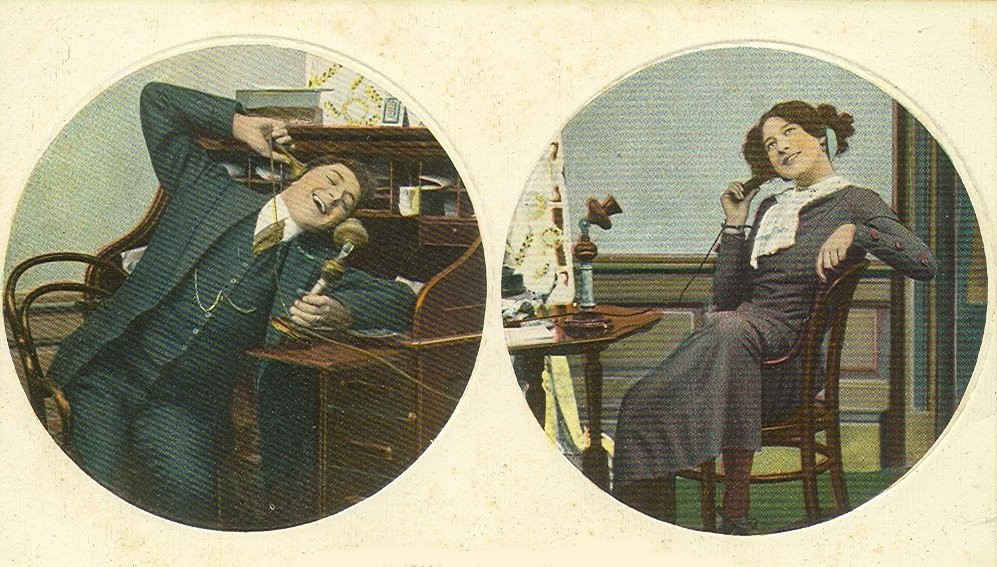

In 1890, as the telephone’s influence spread across the United States, Judge Robert S. Taylor of Fort Wayne, Ind., told an audience of inventors that the telephone had introduced an “epoch of neighborship without propinquity.” Scientific American called it “nothing less than a new organization of society.” The New York Times reported that two Providence men “were recently experimenting with a telephone, the wire of which was stretched over the roofs of innumerable buildings, and was estimated to be fully four miles in length”:

They relate that on the first evening of their telephonic dissipation, they heard men and women singing songs and eloquent clergymen preaching ponderous sermons, and that they detected several persons in the act of practising on brass instruments. This sort of thing was repeated every evening, while on Sunday morning a perfect deluge of partially conglomerated sermons rolled in upon them. … The remarks of thousands of midnight cats were borne to their listening ears; the confidential conversations of hundreds of husbands and wives were whispered through the treacherous telephone. … The two astonished telephone experimenters learned enough of the secrets of the leading families of Providence to render it a hazardous matter for any resident of that city to hereafter accept a nomination for any office.

In 1897 one London writer wrote, “We shall soon be nothing but transparent heaps of jelly to each other.”

(From Carolyn Marvin, When Old Technologies Were New, 1988.)