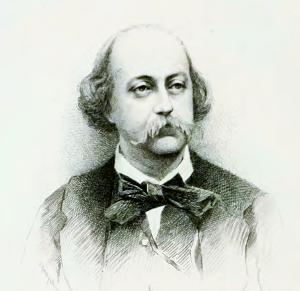

At his death in 1880, Gustave Flaubert left behind notes for a Dictionary of Received Ideas, a list of the trite utterances that people repeat inevitably in conversation:

- accident: Always “regrettable” or “unlucky” — as if a mishap might sometimes be a cause for rejoicing.

- Archimedes: On hearing his name, shout “Eureka!” Or else: “Give me a fulcrum and I will move the world.” There is also Archimedes’ screw, but you are not expected to know what that is.

- bachelors: All self-centered, all rakes. Should be taxed. Headed for a lonely old age.

- book: Always too long, regardless of subject.

- classics: You are supposed to know all about them.

- forehead: Wide and bald, a sign of genius, or of self-confidence.

- funny: Should be used on all occasions: “How funny!”

- gibberish: Foreigners’ way of talking. Always make fun of the foreigner who murders French.

- handwriting: A neat hand leads to the top. Undecipherable: a sign of deep science, e.g. doctors’ prescriptions.

- jury: Do everything you can to get off it.

- metaphors: Always too many in poems. Always too many in anybody’s writing.

- original: Make fun of everything that is original, hate it, beat it down, annihilate it if you can.

- pillow: Never use a pillow: it will make you into a hunchback.

- restaurant: You should order the dishes not usually served at home. When uncertain, look at what others around you are eating.

- taste: “What is simple is always in good taste.” Always say this to a woman who apologizes for the inadequacy of her dress.

- war: Thunder against.

- young gentleman: Always sowing wild oats; he is expected to do so. Astonishment when he doesn’t.

“All our trouble,” he wrote to George Sand, “comes from our gigantic ignorance. … When shall we get over empty speculation and accepted ideas? What should be studied is believed without discussion. Instead of examining, people pontificate.”

(Thanks, Macari.)