In 1799, Massachusetts passed a law restricting private banking companies from issuing their own currency notes without the consent of the legislature. This was well intended: If unlimited paper money were allowed to circulate, the resulting inflation would play havoc with the finances of ordinary people.

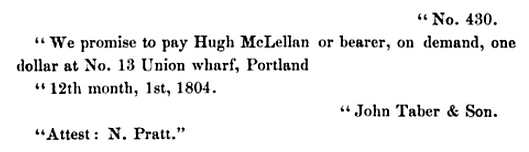

Unfortunately, the result was that legitimate currency became harder and harder to find. In Maine, where only a single bank existed, people were increasingly desperate for currency, and so the Portland merchant John Taber began to circulate notes for 1, 2, 3, and 4 dollars, payable to the bearer in silver on demand, despite the law:

This worked for a while, propped up by Taber’s reputation. But Taber’s profligate son Daniel began to print bills for his own use as he needed them, and when Massachusetts repealed its law John Taber and Son were forced into bankruptcy.

When it was over, Taber approached his old partner Samuel Hussey, who owed him $60. Hussey invited him into his counting room, counted out the amount in Taber’s own now-worthless bills, and asked for a receipt.

Taber said nervously, “Now, thee knows, friend Hussey, this money is not good now.”

“Well, well, that is not my fault,” said Hussey. “Thee ought to have made it better.”

(From the Collections and Proceedings of the Maine Historical Society, 1898.)