Between 1868 and 1870, Mark Twain traveled more than 40,000 miles by rail, dutifully buying accident insurance all the while, and never had a mishap. Each morning he bought an insurance ticket, thinking that fate must soon catch up with him, and each day he escaped without a scratch. Eventually “my suspicions were aroused,” he wrote, “and I began to hunt around for somebody that had won in this lottery. I found plenty of people who had invested, but not an individual that had ever had an accident or made a cent. I stopped buying accident tickets and went to ciphering. The result was astounding. The peril lay not in traveling, but in staying at home.”

He calculated that American railways moved more than 2 million people each day, sustaining 650 million journeys per year, but that only 1 million Americans died each year of all causes: “Out of this million ten or twelve thousand are stabbed, shot, drowned, hanged, poisoned, or meet a similarly violent death in some other popular way, such as perishing by kerosene lamp and hoop-skirt conflagrations, getting buried in coal mines, falling off housetops, breaking through church or lecture-room floors, taking patent medicines, or committing suicide in other forms. The Erie railroad kills from 23 to 46; the other 845 railroads kill an average of one-third of a man each; and the rest of that million, amounting in the aggregate to the appalling figure of nine hundred and eighty-seven thousand six hundred and thirty-one corpses, die naturally in their beds!”

The answer, then, is to avoid beds. “My advice to all people is, Don’t stay at home any more than you can help; but when you have got to stay at home a while, buy a package of those insurance tickets and sit up nights. You cannot be too cautious.”

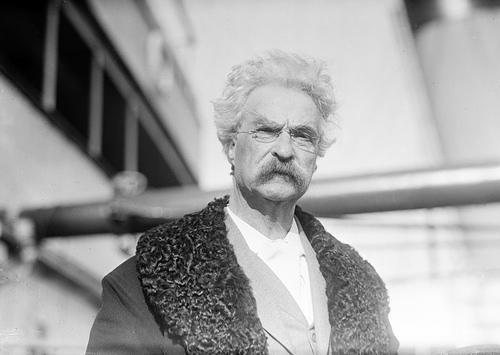

(Mark Twain, “The Danger of Lying in Bed,” The Galaxy, February 1871.)