Every unjust act is inexpedient;

No unjust act is expedient;

No expedient act is unjust;

Therefore every expedient act is just.

— Ralph L. Woods, How to Torture Your Mind, 1969

Every unjust act is inexpedient;

No unjust act is expedient;

No expedient act is unjust;

Therefore every expedient act is just.

— Ralph L. Woods, How to Torture Your Mind, 1969

Oh Lord, Thou knowest that I have lately purchased an estate in fee simple in Essex. I beseech Thee to preserve the two counties of Middlesex and Essex from fire and earthquakes; and as I have also a mortgage at Hertfordshire, I beg of Thee also to have an eye of compassion on that county, and for the rest of the counties, Thou may deal with them as Thou art pleased. Oh Lord, enable the bank to answer all their bills and make all my debtors good men, give a prosperous voyage and safe return to the Mermaid sloop, because I have not insured it, and because Thou has said, ‘The days of the wicked are but short’, I trust in Thee that Thou wilt not forget Thy promise, as I have an estate in reversion, which will be mine on the death of the profligate young man, Sir J. L. …g.

Keep my friends from sinking, preserve me from thieves and housebreakers, and make all my servants so honest and faithful that they may always attend to my interest and never cheat me out of my property night or day.

— John Ward, onetime M.P. for Weymouth, quoted in M.C. D’Arcy, The Mind and the Heart of Love, 1947

(This must be satire, but I haven’t been able to learn anything more about it.)

04/01/2025 UPDATE: Apparently the “prayer” was discovered among Ward’s papers after his death in 1755 — possibly he was condemning self-dealing in Parliament at the time. (Thanks to readers Brieuc de Grangechamps and Jon Anderson.)

If your nose is close to the grindstone

And you hold it there long enough

In time you’ll say there’s no such thing

As brooks that babble and birds that sing

These three will all your world compose

Just you, the stone and your poor old nose.

— “From a two hundred-year-old stone in a country cemetery,” quoted in Christina Foyle, So Much Wisdom, 1984

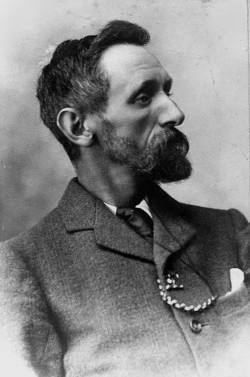

Several claimants have been put forth as the originators of the modern tropical cyclone ‘naming’ system. Australian weather meteorologist, Clement L. Wragge, is one of the best-established holders of the title. … Most ingeniously, he gained a measure of personal revenge by christening some of the nastiest storms with politicians’ names such as Drake, Barton, and Deakin. Modern hurricane researcher Chris Landsea noted that, by using such a personal naming system, Wragge could publicly describe a politician (say one who was less than generous with weather-bureau appropriations) as ‘causing great distress’ or ‘wandering aimlessly about the Pacific.’

— Randy Cerveny, Freaks of the Storm, 2006

Man is so intelligent that he feels impelled to invent theories to account for what happens in the world. Unfortunately, he is not quite intelligent enough, in most cases, to find correct explanations. So that when he acts on his theories, he behaves very often like a lunatic. Thus, no animal is clever enough, when there is a drought, to imagine that the rain is being withheld by evil spirits, or as a punishment for its transgressions. Therefore you never see animals going through the absurd and often horrible fooleries of magic and religion. No horse, for example, would kill one of its foals in order to make a wind change its direction. Dogs do not ritually urinate in the hope of persuading heaven to do the same and send down rain. Asses do not bray a liturgy to cloudless skies. Nor do cats attempt, by abstinence from cats’ meat, to wheedle the feline spirits into benevolence. Only man behaves with such gratuitous folly. It is the price he has to pay for being intelligent, but not, as yet, quite intelligent enough.

— Aldous Huxley, Texts and Pretexts, 1932

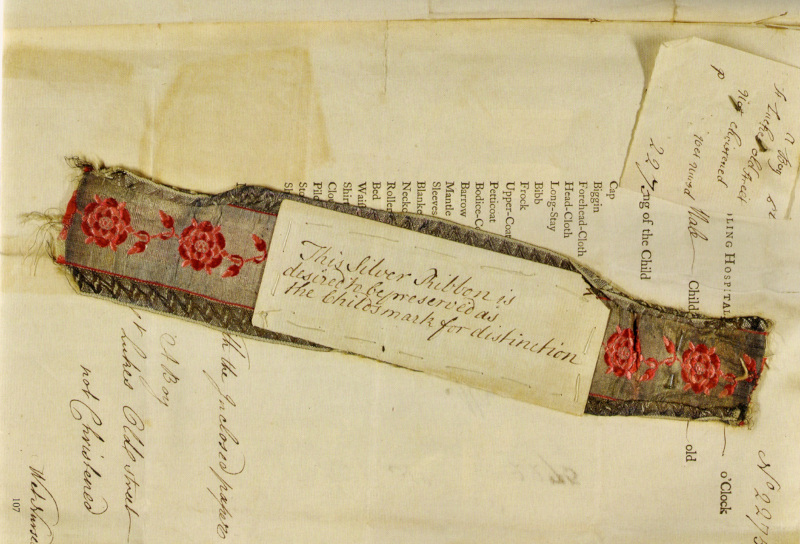

Between 1741 and 1760, when a baby was left at London’s Foundling Hospital, the staff encouraged the mother to provide some token that could be used as an identifying record — a note, a letter, or some other small object. Usually a piece of fabric was provided by the mother or cut from the child’s clothing, and these were attached to registration forms and then bound into ledgers.

Altogether about 5,000 babies received such tokens. The example above bears the message “This Silver Ribbon is desired to be preserved as the child’s mark of distinction.” (Ribbons were recognized symbols of love, especially in circumstances of loss and separation.) Today these pieces of fabric form the largest collection of everyday textiles surviving in Britain from the 18th century.

On the occasion of an exhibition of the surviving swatches at the hospital in 2010, University of Hertfordshire historian John Styles said, “The textiles are both beautiful and poignant, embedded in a rich social history. Each swatch reflects the life of a single infant child. But the textiles also tell us about the clothes their mothers wore, because baby clothes were usually made up from worn-out adult clothing. The fabrics reveal how working women struggled to be fashionable in the eighteenth century.”

“Lady Dillon told Sir F. Chantrey that English women were more buxom than Italian women. The delicate way she put it was, ‘you will find that Italian women can sit much closer to a wall than English.'”

— George Lyttelton’s Commonplace Book, 2002

From Good-Bye to All That, poet Robert Graves’ 1929 account of his experiences in World War I:

Beaumont had been telling how he had won about five pounds’ worth of francs in the sweepstake after the Rue du Bois show: a sweepstake of the sort that leaves no bitterness behind it. Before a show, the platoon pools all its available cash and the survivors divide it up afterwards. Those who are killed can’t complain, the wounded would have given far more than that to escape as they have, and the unwounded regard the money as a consolation prize for still being here.

In 2003, the Journal of Political Economy reprinted this paragraph with the title “Optimal Risk Sharing in the Trenches.”

scribacious

adj. fond of writing

moiler

n. a toiler; a drudge

demiss

adj. downcast; humble; abject

guerdon

n. a reward, recompense, or requital

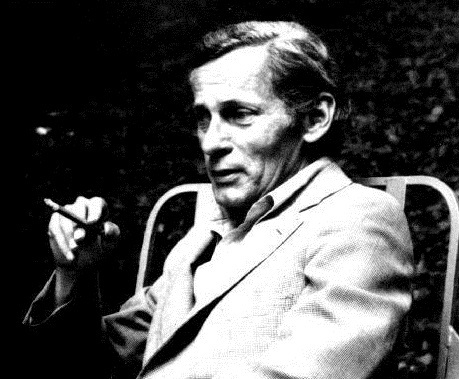

By the end of the 1960s, William Gaddis had secured an advance and an NEA grant that allowed him to work full-time on the novel J R.

“Even then, however, Gaddis would be so in need of money that he would ghostwrite articles for a dentist in exchange for root canals. His son recalls one day happening to find his checkbook, and noting the balance, meticulously calculated, of twelve cents. This was at the time when Gaddis had just won the 1976 National Book Award.”

From Joseph Tabbi’s introduction to Gaddis’ “Treatment for a Motion Picture on ‘Software'” in The Rush for Second Place: Essays and Occasional Writings, 2002.

LADIES AND GENTLEMEN WILL NOT, AND OTHERS MUST NOT, PICK THE FLOWERS.

— Notice, Woodenbridge Hotel garden, County Wicklow, Ireland, 1919