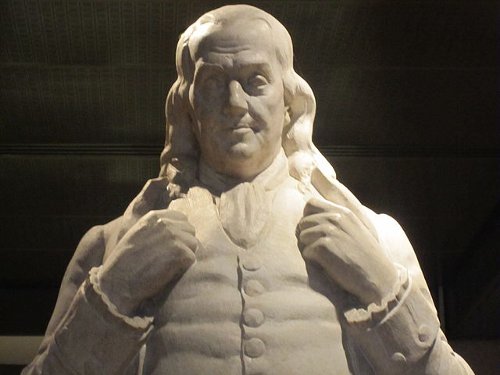

Ben Franklin’s “necessary hints to those that would be rich,” written around 1730:

- The use of money is all the advantage there is in having money.

- For six pounds a year you may have the use of one hundred pounds, provided you are a man of known prudence and honesty.

- He that spends a groat a day idly, spends idly above six pounds a year, which is the price for the use of one hundred pounds.

- He that wastes idly a groat’s worth of his time per day, one day with another, wastes the privilege of using one hundred pounds each day.

- He that idly loses five shillings worth of time, loses five shillings, and might as prudently throw five shillings into the sea.

- He that loses five shillings, not only loses that sum, but all the advantages that might be made by turning it in dealing, which, by the time that a young man becomes old, will amount to a considerable sum of money.

- Again: he that sells upon credit, asks a price for what he sells equivalent to the principal and interest of his money for the time he is to be kept out of it; therefore, he that buys upon credit, pays interest for what he buys, and he that pays ready money, might let that money out to use: so that he that possesses any thing he has bought, pays interest for the use of it.

- Yet, in buying goods, it is best to pay ready money, because he that sells upon credit expects to lose five per cent by bad debts; therefore he charges, on all he sells upon credit, an advance, that shall make up that deficiency.

- Those who pay for what they buy upon credit, pay their share of this advance.

- He that pays ready money, escapes, or may escape, that charge.

- A penny sav’d is two-pence clear, A pin a day’s a groat a year.