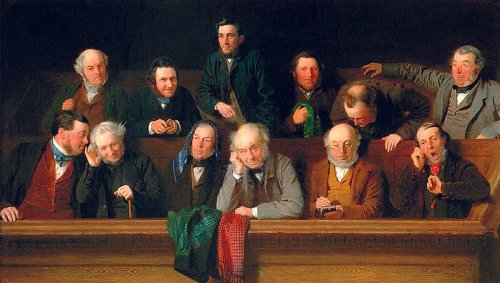

Two or three of them got round me and begged me for the twentieth time to tell them the name of my country. Then, as they could not pronounce it satisfactorily, they insisted that I was deceiving them, and that it was a name of my own invention. One funny old man, who bore a ludicrous resemblance to a friend of mine at home, was almost indignant. ‘Ung-lung!’ said he, ‘who ever heard of such a name? — ang-lang — anger-lang — that can’t be the name of your country; you are playing with us.’ Then he tried to give a convincing illustration. ‘My country is Wanumbai — anybody can say Wanumbai. I’m an ‘orang-Wanumbai; but, N-glung! who ever heard of such a name? Do tell us the real name of your country, and then when you are gone we shall know how to talk about you.’

— Alfred Russel Wallace, “The Aru Islands,” The Malay Archipelago, 1869